After being discharged from the Philadelphia Marine Barracks on July 24, 1945, Lee Marvin, a civilian now, was grappling with a mix of intense emotions – anger, frustration, and, particularly, survivor guilt as the war persisted.

LEE MARVIN – POINT BLANK

On his way back to his family’s Manhattan apartment, an older woman confronted him about not being in the military, to which Marvin, out of instinct, defensively claimed he was physically unfit.

Despite his return home being a cause for celebration, his family struggled to connect with him.

His mother, Courtenay, told Robert that Lee’s war stories were difficult to bear and that it took a solid stomach to listen to them.

Additionally, Lee noticed that his father, Monte, found it even harder to adjust to civilian life.

Lee believed that the war had a devastating impact on his father, stating that it ruined him and left him a broken man.

Although Monte had received a military citation from the British Government during the war, he struggled to secure employment as a civilian.

Also, see Movie-Watching Memories: The Quo Vadis

After a discouraging day of searching for employment, Monte returned to his apartment building on 79th Street, showing little enthusiasm as he greeted the doorman.

Once inside, he prepared a bath but was discovered by the family maid after harming himself. She promptly tended to his wounds and alerted the police.

Subsequently, he was taken to Bellevue in a blaring ambulance for several days of evaluation.

Due to financial constraints, he was placed in a communal ward at the facility, where nightly screams disrupted his much-needed rest.

Despite surviving the suicide attempt, the family never addressed the incident while he was alive.

Monte secured a sales job at the Chicago Tribune through an old friend, prompting the family’s move to the ‘Windy City.’

At his father’s insistence, Lee enrolled in night school to obtain his high school diploma, but he expressed his lack of interest and direction in a letter to his older brother, Robert.

In the letter, Lee conveyed his reluctance towards his current studies and expressed his yearning to explore new, uncharted places like the Yukon.

He expressed a desire to engage in meaningful endeavors. He admitted to contemplating rejoining the Corps, acknowledging that it was driven by a longing to reconnect with the genuine camaraderie he experienced during wartime.

Lee lamented the absence of unexplored frontiers, acknowledging his deep aversion to conforming to societal norms.

Lee faced difficulties in his classes and later reflected, “It was all so absurd. After being involved in killing, finding meaning in peace seemed futile.

How could a person entangled in violence pursue education? It just didn’t add up… I felt I had to do something, but when they tested my typing skills and couldn’t spell half the words, I felt out of place amidst the carefree students.

What was I doing there? So, I quit.” Forty years later, his character in The Big Red One (1979), “The Sergeant,” would convey a distinction by saying, “We don’t murder. We kill,” a concept that was unclear to a young Lee.

When he left school, he walked into a Marine Recruitment Center.

The officer in charge expressed gratitude for his offer and prior service but cited his disability status.

Lee accepted this with a handshake and later laughed it off at a nearby bar. A subsequent physical examination by the military in the fall conclusively deemed his sciatic wound to disable him by 20%.

He received a monthly check of $27.80 for the rest of his life. Monte’s job in Chicago was short-lived, leading the family to return to New York.

Due to the postwar housing shortage in the city, they settled in the Woodstock area, where they had spent summers when Lee and Robert were young.

They purchased a home, and Monte eventually found work nearby with the New York and New England Apple Institute.

Despite sporadic attempts at other employment, he remained with the Institute until his retirement in 1965. Throughout it all, Monte relied on his unwavering work ethic and copious amounts of alcohol to get by.

Located in the foothills of the Catskill Mountains, the Woodstock community had long served as a haven for numerous vibrant avant-garde artists and intellectuals, predating the iconic historical rock concert that occurred in a neighboring town.

The small community boasted three legitimate live theaters at the time: The Woodstock Playhouse, The Valetta Theater, and the 1,000-seat Maverick Theater.

Around the time Robert completed his military service, Lee attended classes at Kingston High School to attain his diploma. Like his childhood, Lee frequently skipped classes to indulge in fishing or hunting.

Monte had envisioned Lee earning his diploma and utilizing the G.I. Bill to pursue a career as an engineer.

However, despite contemplating various professions, such as a forest ranger and car salesman, Lee ultimately disappointed his father once more by dropping out of school, mainly due to the challenges posed by subjects like geometry.

In Woodstock, Lee frequently visited a popular spot known as The S.S. Seahorse, described by a local as the best dive they had ever seen, with people lining up to get in during the summer.

The tavern, shaped like a landlocked ship, was adorned with fitting decor and window portholes. Lee, embraced by local artists and bohemians, was the center of attention in the vibrant social scene.

Amidst the music and laughter, Lee sought temporary solace from his haunting nightmares. According to Robert, Lee would return home unsettled, experiencing convulsions and vividly recounting seeing snipers in the trees or reliving past battles.

At times, Lee would drink at home with his family, where seemingly innocent evenings could quickly turn tumultuous, causing Courtenay to seek refuge elsewhere as tensions escalated.

As the night and alcohol progressed, heated exchanges would arise between Lee and Monte, with both men asserting the superiority of their respective military units, often resulting in physical altercations.

Despite sharing similar struggles, the deep divide between them prevented any reconciliation, and Lee often grappled with guilt and stayed away for days following these family clashes.

Sometimes, he would unexpectedly end up in a bar in Brooklyn, or he would venture to Greenwich Village and spend time with the vagrants who drank throughout the night, using a rope to sleep standing up without being arrested.

The following morning, the rope would be untied, sending everyone sprawling. Lee would then partake in a concoction called “smoke,” a potent mixture of illuminating gas blown into a jar of water that produced a high similar to LSD.

Regardless of his actions, Lee could never distance himself far enough or consume enough alcohol to escape the trauma caused by war or domestic issues.

Upon his return, apologetic as always, the cycle would recommence, often subtly encouraged by Courtenay.

Her efforts to maintain the appearance of domestic happiness led to Lee and the other Marvin men enduring meaningless social gatherings or Sunday afternoon art lectures.

On one occasion, the entire family appeared on local radio for a show about “Thanksgiving in Strange Places,” during which the Marvin men shared their war experiences while a Girl Scout Choir sang in the background.

Regrettably, no recording of the show or the journey home exists.

Monte had become quite well-regarded in the rural community to the extent that he could secure employment for both sons.

By early 1946, Robert was employed by a printer and saving money for college, while Lee became an apprentice to a plumber, working under the guidance of Adolph Heckeroth.

For those interested, Bill Heckeroth, who currently manages his father’s business, is more than happy to show off a cherished keepsake carved into his father’s wall-mounted toolbox: “This belongs to Adolph. Take what you need.”

The carver, of course, was Lee Marvin.

Bill was just a young child when Lee worked for his father, but he fondly recalls the large young man with the booming voice who would prop his feet up on his father’s desk and regale anyone within earshot with captivating stories.

Lee’s tasks included digging septic tanks and hand-threading pipes for a wage of $1.25 per hour. Despite the physical demands, this work proved to be therapeutic.

Marvin later expressed, “A guy digging ditches or a plumber wiping joints, it solves problems, you know? You must dig this hole so vast, so long, so deep.

You dig it, and that’s it. You climb out and say, ‘Boy, I don’t know what it was, but I solved it today.’ Sound therapy for my back.”

Marvin found such solace in this work that he retained his union card even after achieving fame in the film industry and frequently undertook plumbing tasks in his Hollywood agent’s residence.

Adolph Heckeroth genuinely fondled for Lee, impressed by Lee’s innate skill for the job.

On one occasion, when Heckeroth needed Lee’s help to measure the depth of a well, Lee confidently dismissed the old method of using a knotted string and weight, instead boasting that he could simply drop a pebble and determine the exact depth of the well by observing its acceleration.

To Heckeroth’s amazement, Lee’s measurement matched precisely with Heckeroth’s string reading, despite Heckeroth being unaware that Lee had already measured the depth the night before.

During his free time in Woodstock, Lee often socialized with another local, David Ballantine.

Although Ballantine may have seemed an unlikely companion for Marvin due to his small stature, the two shared many common interests. Ballantine met Lee after his discharge from the service in June of 1946.

Reflecting on their friendship, Ballantine humorously recalls Lee’s impressive strength, often showcasing it by performing feats such as lifting Heckeroth’s substantial pipe-cutting tripod single-handedly or raising the front end of a car.

Describing Lee’s personality, Ballantine often likens him to a non-effeminate Clint Eastwood.

While studio biographies have suggested that the Ballantines and the Marvins were close friends, David clarifies that he had only brief acquaintances with Monte and Courtenay, emphasizing that he was primarily Lee’s friend.

However, he acknowledges that Courtenay was amiable, and Monte carried himself with dignity. Lee had once mentioned to David that people would avoid provoking Monte in a bar as he was known to be quite challenging.

David Ballantine didn’t often share his friend’s fondness for alcohol, which he humorously called “the gargle.”

Recalling a few occasions when Lee was heavily intoxicated, David vividly remembers a time when Lee was causing a scene in a bar during a visit many years later.

David took Lee aside and warned him about the potential consequences of his behavior, cautioning him that his actions could lead to a younger version of himself confronting him.

This straightforward advice resonated with Lee, who understood the gravity of the situation and heeded the warning.

On a chilly March evening in 1946, Lee was found sleeping off one of these episodes on a bench in the village green.

As the sun rose, local children, familiar with seeing him in such a state, wisely refrained from disturbing the unconscious figure. However, one bold resident, unaware of the risk or undeterred by it, dared to converse with the prone figure.

When Lee regained his senses, and the haze in his head dissipated, he found himself face to face with a prim and proper young woman discussing the merits of community service.

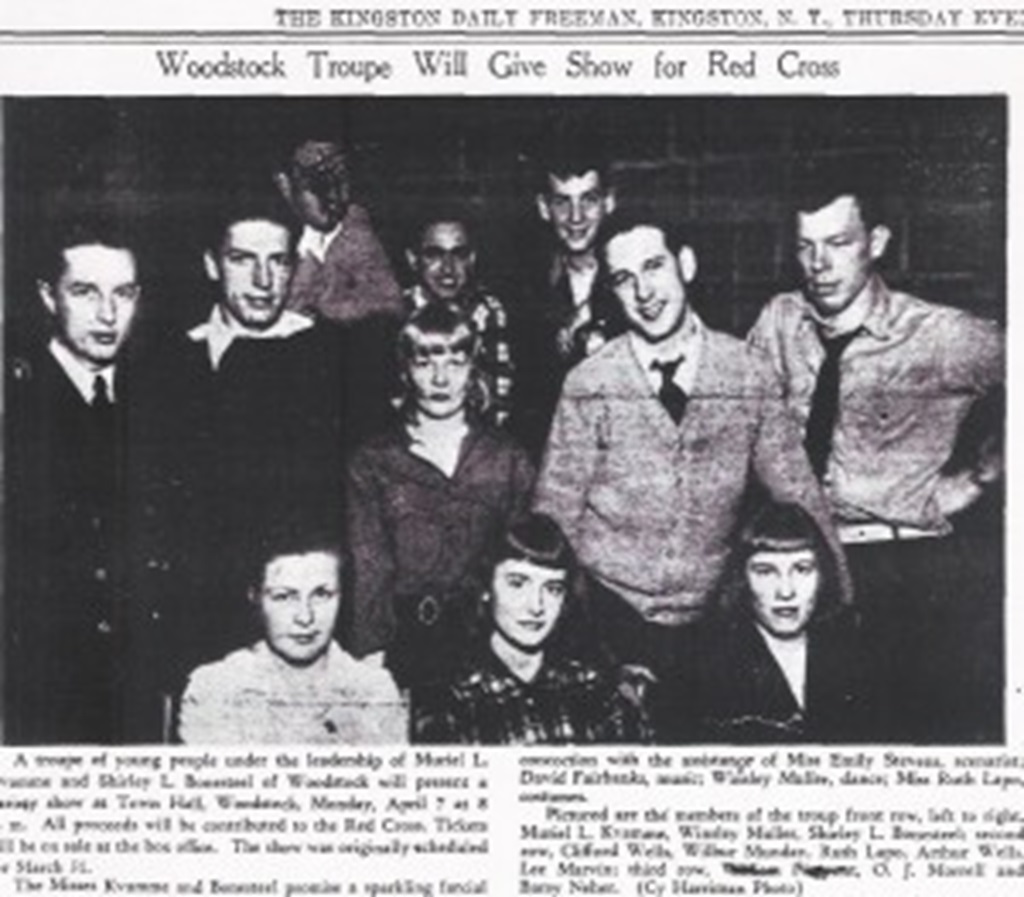

Realizing she was addressing him, Lee couldn’t help but smirk ironically when she invited him to participate in an amateur Red Cross Benefit at Woodstock’s Town Hall, titled “Ten Nights In a Barroom.”

Having been involved in school productions since his early years, Lee found the prospect intriguing and, considering it might provide a similar thrill, nonchalantly agreed to rehearse the farce with his fellow amateur actors over the following weeks.

In 1966, a proud Monte fondly reminisced about Lee’s comical performance, stating, “Lee’s performance was the most hilarious I’ve ever seen.

The mustache kept falling off. Everybody in the cast forgot their lines, and Lee’s hands were very much in evidence, pushing out scripts from the wings. Even then, he left them in the aisles.”

Similar to the legendary tales of Pecos Bill or Paul Bunyan, the account of Lee’s initial foray into professional acting has evolved into a larger-than-life legend, beginning with a nugget of truth and gaining embellishments over time.

Marvin recounted to several interviewers that it was while he had his head in the Maverick Theater commode that he heard his calling to act.

Recalling the moment repeatedly, he said, “The director needed a tall loudmouth to play a Texan.

The actor who played the part was sick. After fixing the head, I was standing in the wings, eyeing this redheaded actress. Later, the director looked at me and figured I was made for the part.”

However, when informed of this account, Monte Marvin disputed its accuracy, stating, “Nothing could be further from the truth since the theater had no toilet, only a one-holer outside.” David Ballantine also supported this assertion.

Regardless, the event that propelled Lee Marvin into acting was equally noteworthy.

When David Ballantine reached the age of twenty-one, his family organized a celebratory birthday gathering in his honor, an occasion that Lee always eagerly anticipated, particularly enjoying the company of the Ballantine family.

David’s brother Ian served as the publisher of Ballantine Books, while his mother Stella played a pivotal role in Lee’s progressive school, Manumit.

Of particular interest to Lee was David’s father, E. J. ‘Teddy’ Ballantine, who boasted an illustrious theatrical background, including involvement in Eugene O’Neill’s Provincetown Players and engaging in drinking sessions with the renowned John Barrymore.

Teddy was also an integral part of the fittingly named Maverick Theater.

Also present at the event was Ian’s wife, Betty, a petite woman renowned for her penchant for donning long, flowing dresses, even in the sweltering summer heat.

She eventually became a confidante to the young Lee Marvin.

Lee himself recounted the events of that evening when his talent for storytelling was still in its infancy: “I got shocked. I was dancing with a girl named Joy, who was 145 pounds, all pink and beautiful.

At the party, I found out the leading man of the local theater had run out on an upcoming production.”

This was the precise moment when E.J. Ballantine discussed the situation with the director and noticed Lee joyfully dancing amidst the other revelers.

Betty Ballantine fondly recollected, “He was an imposing character even then. First of all, there was his voice. His voice was terrific.

Then, he had a natural gift for telling stories with a great sense of humor. He used body language since Lee had extraordinary control of his physical presence.

He was the kind of a person who comes into a room, and you damn well notice him. The play they were preparing was called ‘Roadside.’ They wanted a loudmouth Texan.

Teddy said, ‘We got a loudmouth right here. Hey, Lee! Come over here!’ Of course, we were all feeling no pain. Lee, with that beautiful voice, read for the play.

He got the part and Saturday afternoon and all of Sunday, I sat with him.

Teddy and I both walked him through it. Well, he never really learned the script. How could he? He only had a day and a half.”

Upon hearing his cue on opening night, Lee often exclaims, “It grabbed me just like that!” with a swift snap of his fingers.

He would describe how, at that moment, he suddenly felt a surge of expression. After years of rebellion, concealed fear, and uncertainty, Lee stepped onto the stage that rainy summer night and made it his own.

His commanding voice reverberated through the Hudson Valley like a mild earthquake, signaling to all that he had unearthed his true calling.

Throughout the summer of 1947, Lee wholeheartedly dedicated himself to the Maverick Theater’s summer stock productions.

Reflecting on this period, he later remarked, “It was the closest thing to the Marine Corps way of life I could find at the time – hard work and no nonsense.”

While the camaraderie was significant, acting provided something more for the combat veteran: it offered him a channel to articulate the inner demons plaguing him since the war.

Consequently, he resigned from his job at Heckeroth’s the very next day.

Lee came to a definitive conclusion about his life’s path and decided to confide in his parents.

Monte’s response was immediate and resolute. Recollecting the encounter, Robert stated, “Lee told my father he wanted to be an actor, and my father was naturally taken aback.

He warned my brother, ‘If you become an actor, don’t expect help from me. You’re on your own.'”

While Lee would have preferred his father’s approval, the absence of it only fueled his determination.

In his view, the war had shattered his father, and he was resolute in not succumbing to the same fate. Acting held profound significance for him.

“Acting is a communication search,” he articulated later. “This is what I’m doing — trying to communicate my message.

I can play these parts, these horrible animal men. I do things you shouldn’t do on stage and make you see you shouldn’t do them.”

While many actors enter the profession to express their sensitive nature, Lee Marvin embraced acting to delve into something far more complex: the reservoir of violence that seethed beneath the surface and could erupt at the slightest provocation.

When he portrayed this darker aspect on stage and screen, he did so in a manner that revolutionized the portrayal of modern American screen violence.

Above all else, this would establish Lee Marvin as one of the most enduring and compelling actors of postwar American cinema.