“Walter Mitty and Other Daydreamers” delves into the imaginative lives of individuals who seek solace and excitement within their minds.

Through vivid scenarios and intricate fantasies, these daydreamers escape the mundanity of everyday existence, exploring realms of adventure, romance, and heroism.

Walter Mitty, the quintessential dreamer, embodies the longing for a life more extraordinary.

In this collection, readers are invited to wander alongside Mitty and his fellow dreamers, discovering the boundless possibilities of the human imagination.

Walter Mitty And Other Daydreamers

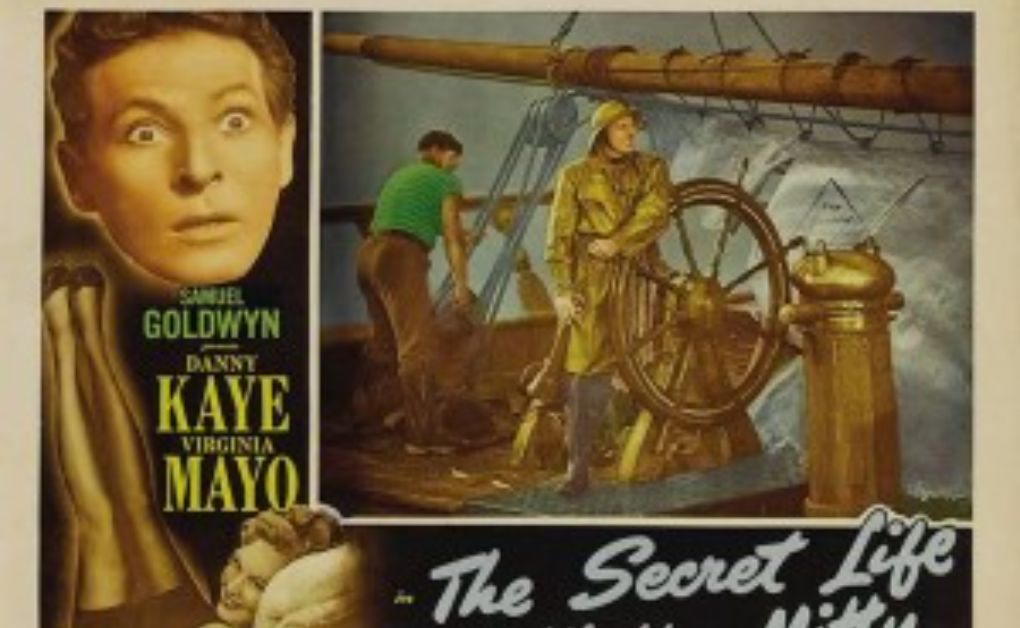

The 1947 Technicolor musical comedy, “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty,” produced by Samuel Goldwyn, features Danny Kaye as an imaginative editor of pulp books.

While it’s not my top pick among Kaye’s works, I suggest opting for a double feature of “Wonder Man” (1945) and “The Court Jester” (1956) if you’re in the mood for a good time.

Despite the film’s various elements not quite coming together, it still offers several enjoyable scenes that warrant a spin on your DVD player.

Critics have easily summarized the plot of “Mitty” as the tale of “a daydreaming everyman” or “a little man with big dreams.”

However, despite the immense popularity of the James Thurber short stories on which the film is based, the character of Mitty wasn’t the first daydreamer protagonist.

Early comedy films often featured a character letting their mind wander into fantastic scenarios, as seen in the 1914 Essanay comedy “Sweedie and the Hypnotist.”

Here, Sweetie (played by Wallace Beery in drag) imagines herself in a whirlwind adventure after being hypnotized at the theater, where she works as a scrub woman.

Though the premise mainly serves as a slapstick comedy setup, it nearly became a nightmare for actor Leo White, who played the hypnotist, as he got trapped in a trunk during filming.

Even in 1914, the plot of “Sweedie and the Hypnotist” was considered cliché.

The image of a janitor daydreaming while leaning on a broom became a recurring motif in comedy films, often inspired by Mark Twain’s novel “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court” from 1889.

In “Hogan’s Aristocratic Dream” (1915), a tramp dreams of being a nobleman in pre-revolutionary France.

Combining both daydreaming genres, “The Knight Watch” (1929) features a movie studio janitor who imagines himself as a gallant knight while watching actors perform on a medieval set.

A story similar to Mitty’s inspired “Reaching for the Moon” (1917).

In this film, Alexis Brown (played by Douglas Fairbanks), a humble clerk in a button factory, dreams of being royalty but realizes by the end that his aspirations are unattainable.

According to the TCM website, the film concludes with Alexis falling off a cliff during a duel, only to wake up and realize it was just a dream.

Disillusioned with his fantasies, Alexis happily returns to his life at the button factory, proposes to his sensible sweetheart, Elsie Merrill, and eventually finds contentment as a family man in a New Jersey suburb.

The underlying message is that indulging in fantasies can be detrimental, and the dreamer should stay grounded in reality.

Buster Keaton explored the realm of daydreams in two of his films.

In “Daydreams” (1922), Keaton’s character ventures to the city to seek his fortune, while his girlfriend, hopeful for his success, imagines him thriving as a surgeon, stockbroker, and police captain based on his vague letters.

Expanding on this theme, Keaton starred in the feature-length film “Sherlock, Jr.” (1924), where he discovers his inner strength by daydreaming himself as a super sleuth.

This more optimistic portrayal of daydreaming set a trend in films that continues today.

Harold Lloyd frequently portrayed daydreamers in his most famous works. In “Girl Shy” (1924), he envisions himself as a master seducer, using his character’s fantasies to parody romantic melodramas of the time.

Similarly, in “The Freshman” (1925), Lloyd’s character yearns for popularity in college and visualizes himself as a campus hero, emulating a figure from a movie poster.

This form of visualization, akin to self-actualization, suggests that one can achieve one’s desired identity by first envisioning it.

Lloyd’s portrayal aligns with Keaton’s idea that daydreams can shape a person’s path to success.

Warner Brothers’ “How Baxter Butted In” (1925), adapted from a 1905 Broadway musical comedy by Owen Davis, served as an early precursor to Mitty. The protagonist, Baxter, a young clerk in a newspaper office, frequently daydreams of heroic feats where he defends his love interest against the villainous office manager. Through these fantasies, Baxter eventually gains the courage to exhibit true bravery. His daydreams facilitate his transformation from a timid failure to a courageous hero.

The story was later remade as “The Great Mr. Nobody” in 1941, with some adjustments to suit contemporary times.

The protagonist, Robert Smith (portrayed by Eddie Albert), nicknamed Dreamy by his friends, similarly fantasizes about performing heroic acts while working as an advertising salesman at a newspaper.

His vivid imagination not only fuels his fantasies but also aids him in creating compelling advertisements. However, Dreamy’s boss takes credit for his ideas, depriving him of recognition and empowerment.

Yet, this lack of acknowledgment ultimately prompts Dreamy to find his courage, take action, and earn the recognition he deserves, culminating in his joining the military.

Key elements of “The Great Mr. Nobody” foreshadowed elements later found in the Mitty film.

Like Dreamy, Mitty is in a fitting profession where his imagination contributes to his success, albeit in writing popular adventure stories for his publisher, a departure from Fairbanks’ character working in a button factory.

However, Mitty also shares the issue of his boss taking credit for his ideas, which is similar to Dreamy’s predicament.

James Thurber’s original story, a mere two and a half pages long, needed more extensive character development, conflict resolution, or a criminal boss.

Mitty, portrayed as a henpecked middle-aged husband with the simple goal of buying puppy biscuits, had a sparse plot that served as the basis for the film.

Thurber’s story resonated with many readers, making it his most famous work. To adapt the thin storyline for a feature film, scriptwriters Ken Englund, Everett Freeman, and Philip Rapp expanded upon the basic premise.

They established Mitty as the only son of an overbearing single mother, which stunted his development and rendered him passive in his relationships.

Unable to assert himself against his mother, boss, or fiancée, Mitty retreats into fantasy to seek the respect and excitement missing from his real life.

In his daydreams, he envisions himself as a fighter pilot, ship captain, riverboat gambler, and Western gunslinger.

So, here’s the scenario: an ineffective man resorts to daydreams to escape his dull reality.

Should we rejoice that this ordinary man can elevate himself and challenge his oppressors through imagination?

Or should we lament that he must seek triumph in a fantasy realm? Is his retreat into daydreams a victory or a defeat?

Keaton and Lloyd have already provided the answer to this question. Instead of daydreams being a means of escape, they reveal a person’s inner power and ambition.

Mitty aims to act upon his fantasies in the expanded story and realize his potential.

Regrettably, Goldwyn’s adaptation of Mitty falters after the initial act. Firstly, the film offers too much polish and glamour for a comedy.

Comedy thrives on sweat, disheveled appearances, and torn clothing. Yet, there are other issues with the film.

The narrative halts whenever Kaye delivers one of his signature patter-songs. These overtly silly numbers, like “Anatole of Paris” and “Symphony for Unstrung Tongue,” are ill-suited for the timid Mitty and are entirely irrelevant to the story.

It might have been more effective if the musical interludes were integrated into the fantasy sequences.

Thurber deemed these musical numbers, which he dubbed “git-gat-giddle songs,” as “deplorable.”

He particularly objected to excluding fantasy scenes, including one where Mitty imagines himself as a trial lawyer and another where he faces a firing squad.

In the original story, Mitty’s fantasy ends with him facing a firing squad. Sylvia Fine, Kaye’s wife and manager, vehemently opposed the trial and firing squad scenes, and her influence prevailed over Thurber’s objections.

Another glaring weakness lies in the film’s leading lady, Virginia Mayo. Despite her Technicolor beauty, Mayo adds little to the film with her lackluster performance.

Sometimes, she appears so wooden that she could be mistaken for a mannequin from Goldwyn’s wardrobe department.

The most significant flaw of the film lies in its daydream sequences, which fall flat. The film features five such scenes, three of which are crammed into the first twenty minutes.

Yet, as the film drags on for another hour and a half, the remaining two daydream sequences are sporadically inserted into the narrative.

It’s as if the filmmakers lost interest in Mitty’s fantasies. Buster Keaton’s appearance as a surgeon in “Daydreams” is immediately comical, but Kaye doesn’t quite fit the bill as a surgeon.

The dream sequences lack the parodic depth expected by viewers. They lack humorous elements, devoid of gags, pratfalls, or witty lines. Kaye’s performance needed to embrace campiness to wink at the audience.

The one instance where the scriptwriters injected humor into a fantasy scene was during Mitty’s surgical endeavors.

Naturally, they couldn’t treat the surgery seriously. Surgeon Mitty employs a ridiculous contraption that goes “ta-pocketa-pocketa-pocketa,” he conducts the procedure using a sock stretcher, a watering can, a cheese grater, and floor wax.

After the initial twenty minutes of the film, Mitty’s daydreams become less prominent as the pulp editor’s real-life adventures surpass the need for fantasy.

His perilous encounters with spies make the fantasy segments redundant. The film could function effectively as a spy comedy without Thurber’s daydream scenes.

Nonetheless, Kaye still delivers comedic brilliance as he grapples with inanimate objects like a chair and a water cooler and desperately tries to evade deadly spies and an enraged husband.

The husband’s fury is warranted as Mitty’s interest in a corset delivered to his wife hides a notebook containing information crucial to thwarting a Nazi plot.

Animator Chuck Jones found success with the daydreaming concept in his portrayal of an imaginative boy named Ralph Phillips in “From A to ZZZ” (1953) and “Boyhood Daze” (1957).

The daydreaming protagonist has remained influential in films such as “Billy Liar” (1963) and “Brazil” (1985), described by director Terry Gilliam as “Walter Mitty Meets Franz Kafka.”

This premise has also lent itself to several television series like “The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin” (1976–1979), “The Singing Detective” (1986), and “Dream On” (1990-1996).

Snoopy from the Peanuts comic strip frequently ventured into Mitty-like territory whenever he imagined himself as a World War I flying ace.

The latest iteration of Mitty aims to be more sophisticated and less frivolous than its predecessor.

While I haven’t yet seen this remake, I’ve seen some reviews.

According to Debruge, “Rather than embracing James Thurber’s satirical tone, [Ben] Stiller approaches it with earnestness, creating what feels like a feature-length ‘Just Do It’ advertisement targeted at restless middle-aged audiences, upon whom its commercial success depends.”

In essence, it takes the notion that fantasies are motivational to an extreme.

Daydreams serve as a rehearsal for our lives and a conduit for releasing creative ideas. Films that celebrate daydreams hold value, though I wish Goldwyn’s Mitty had delved deeper into this concept.