Dennis Hopper’s ascent to fame in Hollywood was swift but equally fleeting. His journey began when he auditioned for a role as a person with epilepsy in the TV series “Medic.”

During the audition, he pretended to have a seizure, impressing the casting director and securing the part, leaving the other actors vying for the role sent home.

While his portrayal of a person with epilepsy may not have been entirely genuine, it reminded his grandmother of the day when he experienced the effects of mood-altering substances as a young boy.

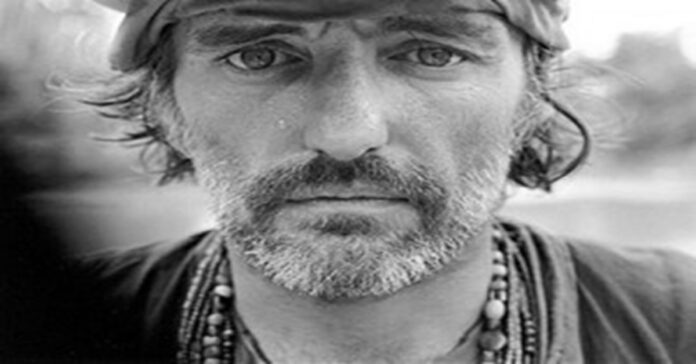

Hopper Dennis

Born in 1936 in the Kansas Dust Bowl, Hopper’s early years were marked by his father’s absence during the war, which led him to believe his father had passed away.

Until age 10, he spent most of his time on his grandparents’ farm, surrounded by wheat fields and devoid of neighbors or playmates.

One day, his curiosity led him to experiment with sniffing petrol fumes from his grandfather’s tractor, an intoxicating experience despite its dangers.

He would regularly lie down on the tractor’s hood, breathing in and gazing at the sky, where he would see the clouds transform into shapes like clowns and goblins.

One day, he had an intense experience where he mistook the tractor’s front for a frightening monster attacking him, prompting his grandfather to intervene.

Unaware of his actions due to being under the influence, he only realized what had happened after his grandparents explained it to him later. This incident foreshadowed a tumultuous life.

Decades later, after a turbulent acting career marked by outbursts and drug-induced episodes, Hopper found himself in a rehab facility where a counselor observed that none of his on-screen characters captured the bewildered, unhinged nature of the man himself.

Hopper once revealed that he pursued acting to escape his unhappy family life and rebel against the rules imposed on him.

His father, who he described as an enigmatic and uncommunicative individual, had faked his death to conceal his undercover work with the OSS in China.

His sudden return after the war left the young boy bewildered, leading Hopper to ponder later whether this experience contributed to his feelings of paranoia.

He recounted that his mother, once an aspiring Olympic swimmer, had to abandon her dreams when she became pregnant with him at the age of 17.

Hopper claimed that his mother directed her frustrations towards him, describing her as emotionally volatile and prone to shouting.

He also admitted having developed a strong physical attraction towards his mother due to her remarkable physique.

Hopper’s introduction to Hollywood began when his family relocated to San Diego, California when he was 13.

Despite being the class clown at school, he secretly pursued acting lessons, much to his mother’s dismay, to escape her disapproval.

He confessed to being a rebellious and troubled youth, associating with a delinquent crowd and engaging in petty crimes.

Still, he found solace in acting, mainly through stage work at the La Jolla Playhouse, where he crossed paths with influential figures like the actor Vincent Price, who introduced him to the emerging Abstract Expressionist art movement.

After his appearance in the TV show Medic, Dennis Hopper encountered a contentious audition with Harry Cohn, the formidable leader of Columbia Pictures.

Hopper reportedly rebuked Cohn for dismissing Shakespeare, leading to a contentious exchange where he told the mogul to “go screw himself.”

Also, see Movie-Watching Memories: The Quo Vadis

In 1955, he quickly secured a role in the groundbreaking film Rebel Without a Cause alongside the emerging stars James Dean and Natalie Wood, an experience that significantly impacted Hopper.

Dean’s magnetic presence captivated him, while Wood introduced him to a lifestyle marked by excessive behavior, leading to distressing repercussions when she attempted to initiate an orgy in a bath of champagne.

Wood’s parents, Nick and Maria Gurdin were Russian immigrants, with Nick working as a carpenter struggling with alcoholism.

Maria harbored aspirations for wealth and fame, which materialized when a film crew visited their hometown in northern California.

Seizing the opportunity, she orchestrated a meeting between her four-year-old daughter and director Irving Pichel, impressing him with a Russian folk song sung by Natalie.

This resulted in a brief walk-on role for Natalie, prompting Maria to relocate the family to Hollywood, where she skillfully steered her daughter into her first speaking role and a successful career as a child actress.

As Rebel Without a Cause approached, Wood was 16 years old, caught in an awkward stage of being too mature to portray children but too young to take on leading roles opposite older male actors.

Her domestic life was challenging, with her father experiencing bouts of drunken outbursts and even pursuing his wife around the house with a butcher knife.

Meanwhile, her mother prohibited anything that could jeopardize her daughter’s potential success as an actress, including relationships with boys her age.

Reflecting on her upbringing, Wood later revealed, “I was a rather obedient child,” expressing how her parents initially objected to her involvement in Rebel due to its unflattering portrayal of parents.

Yet, after reading the script, she felt a strong pull towards the role, recognizing a connection with Judy, a teenager from a dysfunctional family central to the film’s narrative.

The director of Rebel, Nicholas Ray, aged 43 at the time, was a bisexual, womanizing misogynist with addictions to alcohol, drugs, and gambling.

Wood, attempting to project a mature and seductive image, visited his office heavily adorned with makeup, dressed in what she believed was the most alluring attire, and perched on high heels, trying to gain his favor.

However, her efforts did little to alter Ray’s perception of her as a child actress, although she eventually found herself in his bed at the Chateau Marmont Hotel on the Sunset Strip.

Ray frequented a poolside bungalow where he engaged in afternoon liaisons with compliant young actresses, including well-known figures like Marilyn Monroe and Jayne Mansfield, who were also being considered for the role of Judy.

Ray eventually agreed to conduct a screen test with Wood and Hopper, which transpired on a rainy evening, leaving both actors feeling despondent and drenched, as Hopper later reminisced.

The following day, Wood contacted Hopper via telephone, reminding him of their screen test together, emphasizing the rainy backdrop to jog his memory.

The slender youngster was hardly recalled by Hopper “because I tested with about ten women that day.”

However, she had a great sense of humor. She told me that I was beautiful, that she thought I was fantastic, and that she wanted to have sex with me.

Being that assertive as a woman in the 1950s was truly remarkable. For starters, I found it to be an incredible turn-on. However, it was unquestionably at odds with every thought or trend of the day.

Hopper pulled up to a lover’s lane to make out after picking Wood up from Ray’s hotel, where she had spent the afternoon with the director.

Just as he would fall on Natalie, she cried, “Oh, you can’t do that.” “Why?” said Hopper. “Because Nick just fucked me,” the woman stated.

During an interview, Hopper recalled feeling uneasy about the situation when he was 18.

He found it odd that Wood, who was having an affair with a minor, was involved with him. Even though their relationship was also illegal due to his age, he felt it was less problematic as he was only a few years older.

Wood acted as Hopper’s guide to Hollywood, driving him around in her pink Ford Thunderbird alongside Rebel cast member Nick Adams.

They engaged in activities such as placing their hands and shoes in the imprints of famous actors at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre.

Without James Dean’s response to her interest, Hopper became Wood’s substitute, as they shared a resemblance and a dedication to the Method school of acting.

The duo oscillated between seeking seriousness and enjoyment. They watched foreign films to explore new ways of working and were driven by ambition to bring about change.

They also aspired to follow in the footsteps of show business legends and began to imitate what Hopper described as “wild, crazed Hollywood icons.”

According to Hopper, they were almost naively convinced that indulging in drugs, alcohol, and promiscuity was linked to creativity, which was their ultimate goal.

He noted that Wood always aspired to excel. Hopper expressed their envy towards the previous generations, notably the rebellious figures of the Fifties, such as John Barrymore and Errol Flynn, both of whom met tragic ends due to alcoholism.

He revealed that they perceived the self-destructive lifestyles of these Hollywood icons as romantic and vibrant.

The stories of John Garfield’s orgies and the concept of “Hollywood roulette” fascinated them, leading them to try and replicate that way of life. Peculiarly, they attempted to imitate a bygone era of glory.

Hopper and Nick Adams leased a residence in the Hollywood Hills, where, together with Wood, they aimed to outdo the wild behavior of the famous individuals who came before them.

Hopper recounted an instance when he and Natalie planned to host an orgy.

One of the attendees was Hopper’s high school friend, Bob Turnbull, who remembered, “It was quite a significant occasion. She desired the participation of various men.”

Hopper explained that WWood expressed her desire for a champagne bath, as she had heard that someone like Jean Harlow had indulged in one.

Consequently, Nick and Hopper obtained a lot of champagne, filled the bathtub with it, and informed Wood that they were prepared for the planned gathering.

Wood then disrobed, settled into the champagne-filled bathtub, and screamed.

Why did she scream? Hopper explained, “Well, because it burned her, you know, set her on fire.” Hopper and the others hurried Wood to the nearest emergency room, where she received treatment for a severe burn.

“Of course, there were other occasions when Dennis, Nick, and I would also be enjoying her company,” Turnbull commented.

“She was simply an adventurous and lively woman. She was very sociable but had a strong sexual appetite. She was a sophisticated individual with a completely different perspective on morality. She was kind, polite, and had a very uninhibited nature.”

Hopper experienced feelings of sexual jealousy towards the director of “Rebel.” Hopper confided in Steffi Sidney, a friend, that he sought out Wood at Ray’s bungalow one evening and discovered them being intimate.

“He confided in me about his love for Natalie and his intentions, as Nick despised him,” Sidney revealed.

Hopper claimed that he went to the Chateau Marmont with a firearm to confront Ray, but fortunately, Ray was not at home that night.

The hatred spilled over onto the film set: Ray attempted to dismiss Hopper and cut much of the dialogue from his role as Goon, a gang member.

However, Hopper’s experience was profoundly impacted by observing Dean at work on the Rebel set. “I thought,” Hopper remarked, “I was the finest actor in the world — the finest young actor.

Until I saw James Dean, he captivated me. Dean completely disregarded any direction in the script. He would interpret a scene differently every time. It stemmed directly from his imagination, his improvisation.”

Hopper attempted to engage Dean in conversation about his technique, but Dean preferred to remain in his dressing room, smoking marijuana and listening to classical music.

“I tried to connect with him. I started with a simple ‘Hello.’ No response.”

Hopper recounted that he eventually caught Dean’s attention by throwing him into the back seat of one of the cars used in the “chickie run” scene.

Hopper developed a mentor-student relationship with Dean, sharing experiences with peyote and marijuana. “He started observing my takes,” he recalled. “I wouldn’t even realize he was there.

He would approach and mutter, ‘Why don’t you try it this way?’ And he was always correct.”

The 24-year-old Dean lost his life in a fatal car accident when he crashed his Porsche 550 Spyder on September 30, 1955, just a month before the release of Rebel.

The impact of his death on Hopper cannot be overstated, as he once spoke of Dean as if he were the love of his life: “I spent almost every day with him during the last eight months of his life, and then he died.

Dean’s death haunted me; it was the most profound emotional shock of my young life. He taught me so much. When he died, I felt robbed. I had placed my dreams in him, and suddenly that was shattered.

Alcohol and drugs provided temporary respite. That was the first significant event that genuinely affected me… My life was in disarray and confusion for years.”

Dean’s immediate influence led Hopper to believe he could exert the same influence on set as his idol. Hopper perceived Dean had a significant sway over Nick Ray and made creative decisions on Rebel.

However, Hopper realized he was not on the same level as Dean.

In 1957, he found himself in a significant confrontation with experienced director Henry Hathaway while filming From Hell to Texas.

Following the example set by Dean, Hopper resisted conforming to the director’s methods. Hathaway eventually wore him down when they spent an entire day filming 87 takes of a 10-line scene.

This experience effectively led to Hopper’s exclusion from Hollywood studio films.

Hopper tied the knot with Brooke Hayward and worked intermittently in episodic television and low-budget films. He directed his creative efforts into photography and the collection of Pop Art.

He also shot second-unit footage of Peter Fonda in The Trip and collaborated with him on Easy Rider, which unexpectedly became a hit in 1969.

Before Easy Rider, Hopper was seen by the Hollywood establishment as “a maniac and an idiot and a fool and a drunkard.”

However, after the success of Easy Rider, he suddenly became the leading figure in the youth market. He was granted complete creative freedom to direct his next project, The Last Movie.

Recalling the making of The Last Movie, a disastrous venture filmed in Peru in 1970, Hopper described it as a prolonged period of excessive indulgence in sex and drugs.

Hopper stated, “Everywhere you looked, there were intoxicated, naked individuals. There was a large amount of cocaine, and we consumed it all.

But I wouldn’t say it hindered the movie. I’d say it helped us complete the movie. We might have been substance abusers, but we were substance abusers with a purpose and a strong work ethic. It was all about the movie.

If we were going to use drugs and engage in intimate activities, we would do it on camera. The drugs, the alcohol, and the wild sexual encounters all fueled our creativity. At least, that’s my justification.

If you’ll be that depraved, having a good reason is better.”

Hopper spent more than a year socializing with a hippie group while editing The Last Movie at his new Taos, New Mexico residence.

He married singer Michelle Phillips on Halloween in 1970. However, she left him soon after, alleging that he had restrained her, called her a witch, and discharged firearms inside his house.

The Last Movie, an incoherent and pretentious debacle, failed to resonate with audiences and critics and flopped, dragging Hopper’s career down.

Hopper isolated himself in Taos, occasionally working on films outside the U.S., such as Mad Dog Morgan, The American Friend, and Apocalypse Now.

The lowest point arrived in 1982.

“I was consuming half a gallon of rum with an additional fifth of rum, 28 beers, and three grams of cocaine per day — and that wasn’t for getting high, it was just to keep functioning,” he stated.

“It felt like a nightmarish, paranoid, schizophrenic journey that was utterly insane.”

Suffering from delusions and convinced that the mob had issued a contract on his life, Hopper staged an old rodeo stunt known as the Russian Suicide Death Chair at a speedway in Houston to promote a retrospective of his art at Rice University.

He sat on a chair wired with dynamite sticks and ignited the fuse. Remarkably, he emerged from the explosion unharmed.

A German producer sought Hopper for a movie about a group of models held captive by a South American drug lord, offering him more money than he had ever been offered before.

He traveled to Cuernavaca, Mexico, where the film would be produced. However, this venture marked the beginning of Hopper’s descent into madness.

“My manager had advised them not to give me any alcohol, so I couldn’t get a drink and started experiencing hallucinations,” he explained.

The three complimentary shots of tequila left for him in his hotel room pushed Hopper over the edge. He later claimed that they were laced with LSD.

“I became convinced that there were individuals in the depths of this place who were being tortured and cremated,” he recounted.

“The people who had come to rescue me were being killed and tortured, and I believed it was my fault.”

He fled into the balmy Mexican night, but the hallucinations persisted. He self-gratified with a tree, believing he was forming a galaxy. He experienced sensations of insects and snakes piercing through his skin.

Stripping off his clothes, he wandered into the rural landscape, witnessing enigmatic lights that he mistook for extraterrestrial spacecraft.

Hopper walked back to town in his underwear as morning broke, pelting passing automobiles with pebbles.

“I refused to be dressed when the police tried to get me dressed,” he stated. “No, don’t kill me in this manner! “I want to pass away nude.”

Some members of the film crew arranged for his return to Los Angeles. “During the flight, I experienced hallucinations and ended up crawling onto the wing midair,” he recounted.

“I was convinced that Francis Ford Coppola was present, filming me. I had seen him and the cameras, so I was sure they were there.

The crew even set the wing on fire, and I crawled onto it, believing they were capturing me on film. I was out there, and a group of stuntmen pulled me back in.”

Hopper awoke in a straitjacket in a psychiatric ward, surrounded by other celebrities in similar restraints who were screaming.

“I need to quit drinking,” he told himself. An antipsychotic medication caused him to experience symptoms resembling Parkinson’s disease. It took him excruciating minutes to eat or smoke.

He renounced alcohol but covertly continued consuming substantial quantities of cocaine — “half an ounce every two to three days at most” — and then descended into complete madness: “It’s truly astounding when the telephone wires begin speaking to you.”

Hopper eventually reflected on his actions. “I had rationalized heavy drinking and drug use, believing that as an artist, it was acceptable,” he explained.

“The truth was that I was simply an alcoholic and a drug addict. It didn’t help me create; in fact, it hindered me. It impeded my job opportunities. I coped with rejection by turning to more alcohol and drugs. All they brought me was a great deal of misery.”

A year after Hopper embraced sobriety, David Lynch, known for his expertise in the macabre and his ability to infuse mundane situations with impending dread, cast him as the volatile, gas-inhaling drug dealer Frank Booth in his new film, Blue Velvet, without even meeting the actor.

Hopper assured Lynch over the phone that he comprehended the role.

“I am Frank,” he told Lynch, a statement that gave the director some pause. Hopper perceived the film as a love story, elaborating, “I understood his [Booth’s] sexual fixation.

But I saw him as a man who would go to any lengths to protect his lady.”

His unparalleled portrayal became his defining role, overshadowing his previous work. It would ultimately become both a blessing and a curse.

Despite maintaining a busy schedule afterward, he found himself pigeonholed into portraying endless variations of Frank Booth for the remainder of his life.

Before passing away at the age of 74 due to prostate cancer, he reflected, “Let’s see, I guess, Easy Rider, Blue Velvet, a couple of photographs here, a couple of paintings… those are the things that I would be proud of, and yet they’re so minimal in this vast body of crap — most of the 150 films I’ve been in — this river of excrement that I’ve tried to turn into gold. Very honestly.”