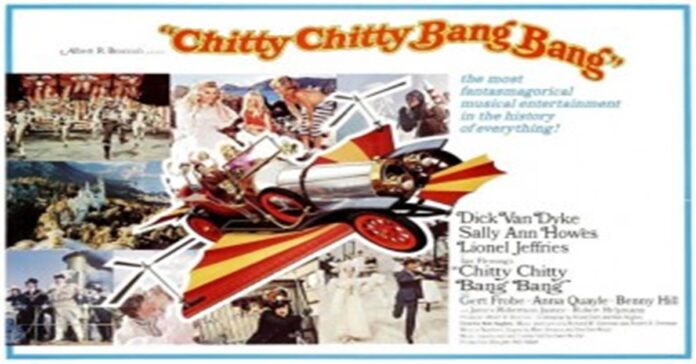

“Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968)” is a beloved family musical adventure film based on the novel by Ian Fleming. Filled with whimsy, enchanting musical numbers and memorable characters, the movie has charmed audiences for decades with its timeless appeal.

The film was directed by Ken Hughes, a versatile filmmaker known for his work in various genres, including dramas, thrillers, and musicals.

Hughes was acclaimed for his ability to bring imaginative and visually stunning storytelling to the screen, and “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang” is a testament to his skill in creating magical and captivating cinematic experiences.

Also Read More: Who Is Mojo Nixon Wife Adaire? Kids Ruben And Rafe

Chitty Chitty Bang Bang: A Historical Perspective on Personal Flying Devices in Literature and Folklore

Throughout history, humankind has been fascinated with personal flying conveyances, as evidenced by various cultural representations.

In Indian epic poems from late Antiquity, flying chariots, or “sun chariots,” were described, while folk tales depicted individuals soaring into the sky on magic horses.

Samuel Brunt’s 1727 novel “A Voyage to Cacklogallinia” featured a character ascending to the moon in a palanquin carried by human-sized birds.

These devices’ most iconic flying carpet was an enduring element of adventurous fairy tales within the Parthian Empire.

Initially depicted as a weapon of war, flying carpets were central to numerous folk tales, including stories of surprise attacks on enemy kingdoms.

The concept gained international fame when featured in Middle Eastern folk tales such as “The Three Brothers” and “Aladdin and The Magic Lamp,” which were later associated with the latter tale.

Jules Verne, a pioneer in portraying flying cars, envisioned such vehicles in his novels.

In “All Around the Moon” (1870), he described a journey to the moon in a flying car, while “Master of the World” (1904) featured the Terror.

The enduring appeal of personal flying devices in literature and folklore reflects humanity’s enduring dream of personal airborne travel, as depicted throughout various cultural narratives.

Early filmmakers initially portrayed flying cars in a humorous light. The 1906 British comedy “The ‘?’ Motorist” is recognized as the earliest film featuring a flying car, depicting a motorist evading a police officer by driving up a building and flying into space.

In the 1923 comedy “Skylarking,” a car is lifted into the sky by a hot air balloon, adding to the early cinematic depictions of airborne vehicles.

Early Hollywood stunt performers ingeniously created the illusion of flying cars without relying on special effects.

Additionally, the concept of flying cars was integrated into futuristic cityscapes, as demonstrated in the 1927 film “Metropolis” by Fritz Lang, where small personal airplanes were seen navigating amongst buildings, setting a precedent for portraying flying cars as a futuristic element in cinematic landscapes.

This trend has persisted in film, serving as a distinctive feature to establish futuristic settings.

The cartoon “Happy Days” (1936) by Ub Iwerks showcases a car that levitates into the sky when its tires are overinflated, and this cartoon is available on YouTube.

The flying car gained significant attention with the release of “The Absent Minded Professor” (1961), where Professor Ned Brainard invented flying rubber, or “Flubber,” which allowed his Model T to fly.

The film’s special effects supervisors, Robert A. Mattey, and Eustace Lycett, received an Academy Award nomination for their masterful use of miniatures and screen matte effects.

The success of “The Absent Minded Professor” sparked a trend in flying car portrayals, notably seen in “Invasion of Neptune Men” (1961), where a superhero named Space Chief battles an invading army from outer space in a rocket-propelled car. This trend also extended to television.

In the French film “Fantômas se déchaîne” (1965), the arch-villain Fantomas escapes in a Citroën DS equipped with retractable wings that transform it into an airplane.

This innovative concept, influenced by popular gadgets featured in James Bond films, showcased the iconic Citroën DS, known for its futuristic aerodynamic design. It has remained a celebrated movie prop for the last fifty years.

Recently, this flying car was featured in a short comedy film depicting Fantomas in grease-stained red overalls as he struggles to repair his iconic flying car.

Evolution of Flying Cars in Cinema: From Chitty Chitty Bang Bang to Blade Runner

When “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang” arrived, the flying car concept was already familiar.

Initially, it appeared similar to “The Terror” vehicle. Still, its unique twist was revealed as it was endowed with independent intelligence and the ability to respond to threats with various devices efficiently.

Renowned production designer Ken Adam, notable for his work on early James Bond films and “Dr. Strangelove,” along with cartoonist and sculptor Frederick Rowland Emett, designed the car to be more fanciful than the flying Model T in “The Absent Minded Professor.”

Taking advantage of filming in Technicolor, the car’s design featured eye-catching crimson red wheels and upholstery, wavy-edged wings with red and yellow stripes, and features like flotation devices and propellers.

Despite the effort put into its design, the flying car had limited appearances in the film, and its traveling matte effects were deemed inferior.

This was unexpected given that the special effects were supervised by John Stears, who had received Academy Awards for his work on “Thunderball” and later “Star Wars.”

In a James Bond film, “The Man with the Golden Gun” (1974), a flying car played a significant role, aligning with the future of marketing and travel.

Inspired by an actual flying car prototype, the production utilized 15 vehicles the American Motors Corporation provided for product placement.

However, the actual flying capability of the car fell short, leading to the creation of a remote-controlled scale model for aerial scenes.

Subsequent films like “Star Wars” (1977) and “Blade Runner” (1982) featured personal flying vehicles, including airspeeders and agile flying cars known as Spinners.

The Spinner’s design, conceptualized by industrial designer Syd Mead and built on a Volkswagen chassis by automotive designer Gene Winfield, allowed for vertical takeoff, hovering, and jet propulsion for aerial maneuvering.

“Repo Man” (1984) introduced a 1964 Chevrolet Malibu with the ability to fly, further expanding the representation of flying cars in cinema.

In “The Last Starfighter” (1984), a teenage boy is taken away from his home in a flying car referred to as the “Star Car,” designed based on the DeLorean automobile.

A similar flying car concept reappeared in “Back to the Future” (1985), where an old man whisks a teenage boy away in a flying car functioning as a time machine, also based on the DeLorean.

The flying DeLorean, inspired by the Star Car, was constructed for “Back to the Future Part II” (1989) by Gene Winfield, who had previously designed and built the Star Car.

Winfield utilized molds from a DeLorean to create a 700-pound fiberglass model. Additionally, vehicles from various films, including the Star Car, a Spinner from “Blade Runner,” and others, were brought in to dress the sets representing the 2015 version of Hill Valley.

Mel Brooks parodied the flying car trend by featuring a flying Winnebago in “Spaceballs” (1987). In the same year, “Doctor Who” introduced a flying bus in the episode “Delta And The Bannermen,” contributing to portraying heavy-load vehicles taking flight in legitimate science fiction films.

The “Star Wars” universe incorporated hover trucks, while “The Fifth Element” (1997) showcased a squadron of flying cars engaged in a police chase through a futuristic New York.

This scene, employing a masterful blend of miniatures, CGI elements, and digital matte paintings, aimed to present a more utopian future vision than “Blade Runner.”

Subsequently, a flying car appeared in “Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets” (2002), delighting children with its magical presence.

The producers of “Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer” (2007) collaborated with the Chrysler Group to debut the comic book heroes’ flying car, The Fantasticar, boasting advanced features such as the ability to split into three independent sections and travel at speeds of up to 550 miles per hour.

These instances illustrate the diverse and evolving portrayal of flying cars in cinema, ranging from parodies to fantastical and futuristic renditions, adding layers of innovation and excitement to the cinematic universe.

In 2009, Russian film company Bazelevs Productions succeeded with “Black Lightning,” a superhero film featuring a college student who combats crime using a flying car. Universal is presently working on an English-language remake of the film.

In “Captain America: The First Avenger” (2011), Stark Industries, a government contractor, presents a flying car prototype, adding to the representation of flying cars in the superhero genre.

Chrysler reentered the flying car arena with a significant marketing investment in “Total Recall” (2012).

The film’s production designer, Patrick Tatopoulos, collaborated closely with Chrysler on design decisions, occasionally needing adjustments to align with the company’s preferences.

During the filming of “Total Recall,” the hovercars were mounted on rigs and driven at high speeds beneath the Gardiner Expressway in Toronto and at an unused Canadian air base in Borden.

Visual effects supervisor Adrian de Wet mentioned the rigorous filming process, including driving the cars at 40-50 miles an hour and digitally removing the rigs in post-production.

The trend of flying cars continued with Russell T Davies’s 2012 show “Wizards vs Aliens,” reflecting the widespread inclusion of flying cars in futuristic settings in contemporary cinema and television.

The portrayal of mass-produced flying cars in futuristic cityscapes has become a standard expectation in filmmaking, reflecting a belief in the inevitability of flying cars as a part of future landscapes.

However, while filmmakers present flying cars as a natural aspect of futuristic settings, some individuals, like myself, continue to view agile flying cars as an enjoyable fantasy element primarily experienced through quality fantasy films.

Also Read More: Paul Faye Tennessee Wikipedia And Age: Where Is He Now?