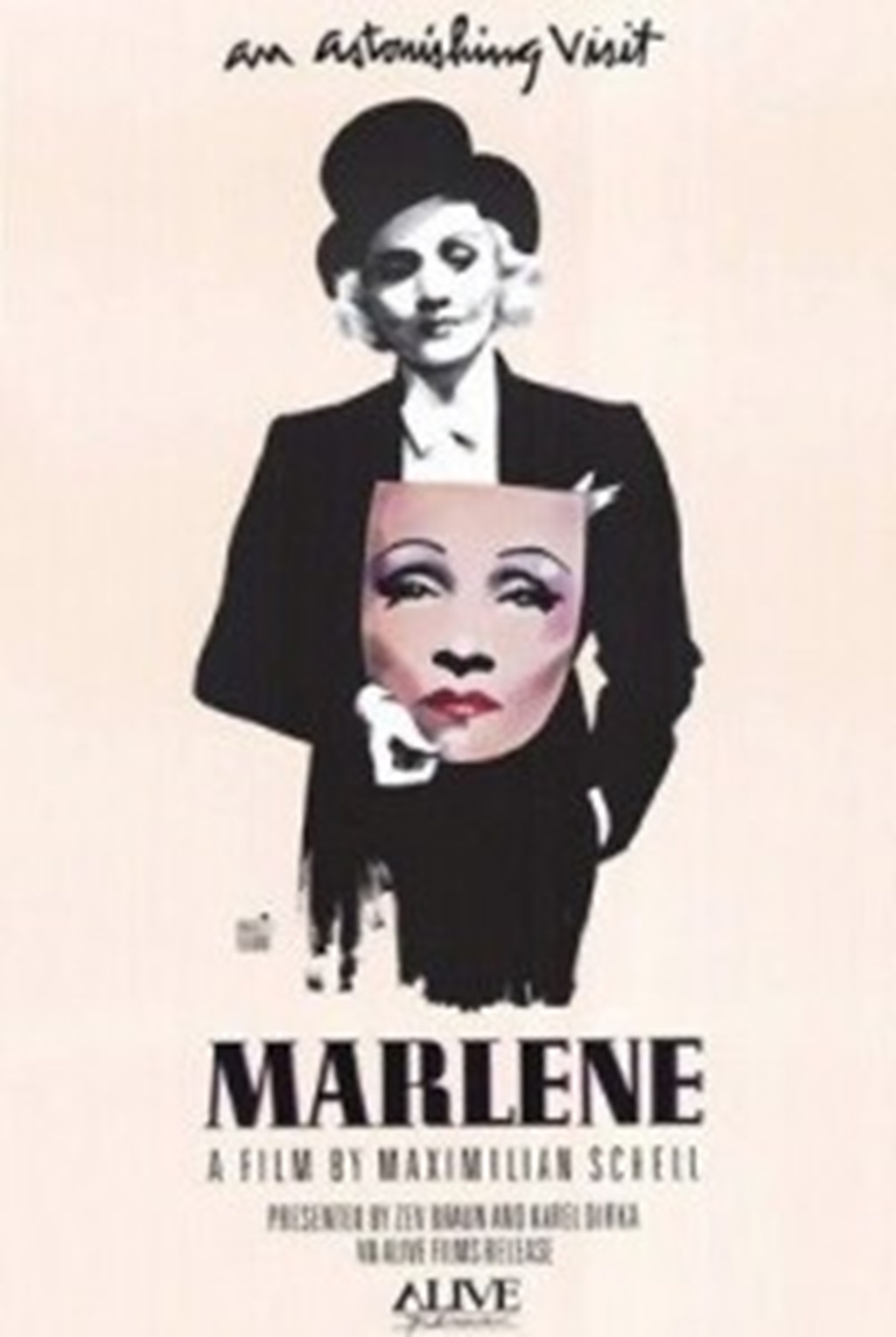

Marlene is a 1984 documentary directed by Maximilian Schell that offers a captivating glimpse into the life and enigmatic persona of the legendary actress and singer Marlene Dietrich.

Through innovative filming techniques and intimate conversations, the documentary provides a unique perspective on the iconic star’s career and personal life, compellingly portraying this influential figure in entertainment history.

Marlene Dietrich was a German-born actress and singer who achieved international fame for her distinctive voice, elegant style, and androgynous allure.

Rising to stardom in the early 1930s, she became known for her roles in classic films such as “The Blue Angel” and “Morocco.”

Dietrich’s unconventional persona and contributions to cinema and music influence popular culture today.

Also, see Blu-Ray Review: Martin Scorses’s World Cinema Project No. 3, From The Criterion Collection.

Marlene

Marlene Dietrich, who lived from 1901 to 1992, probably believed no one would want to watch a documentary about her life and work.

Her entertainment career spanned 55 years, beginning with roles in German films in 1923 and ending in 1978 with her performance of the title song in the movie “Just a Gigolo.”

It’s possible that she didn’t want to look back on her time as a mysterious actress and cabaret singer. She often referred to most of her work as “kitsch.”

However, in the 1984 film “Marlene” by Maximilian Schell, Dietrich doesn’t come across as negatively as she portrays herself. Nonetheless, she made it challenging for others to work with her.

To begin with, Dietrich declined to be filmed. She stated, “I’ve been photographed enough. I’ve been photographed to death.”

This could have been a significant obstacle for any documentary, but director Schell, who had acted with Dietrich in 1961’s “Judgment at Nuremberg,” used this to his advantage.

Schell recorded Dietrich’s conversations on audio tape in her Paris apartment 1982. He recreated the apartment interior and an adjoining editing room a year later.

It was an innovative and clever approach, although sometimes it may have seemed pretentious. In some respects, “Marlene” is a documentary about the process of making a documentary.

In his portrayal of Dietrich in 1982, Schell immerses the audience in the legend depicted through iconic film clips, newsreel footage, and television excerpts, as well as engaging in multilingual interviews with Dietrich.

These interactions often resemble a verbal duel, with Schell’s questions being as aggressive as Dietrich’s responses.

Despite Dietrich’s insults, the documentary provides ample coverage of her cinematic milestones, from her breakthrough role as Lola in “The Blue Angel” to her memorable performances in “Blonde Venus,” “The Scarlet Empress,” and “Destry Rides Again.”

However, Schell faces obstacles in discussing Dietrich’s partnership with von Sternberg, which she dismisses, directing him to her memoir.

Despite this, the documentary sheds light on Dietrich’s evolution as an actress during her Hollywood years, showcasing her exceptional performances in films such as “Witness for the Prosecution,” “Touch of Evil,” and “Judgment at Nuremberg.”

Additionally, it highlights her captivating presence in later television appearances, where she mesmerizes audiences with her unique singing style.

Schell captures Dietrich’s enigmatic persona, revealing her sentimentality and emotional moments, including her nostalgic recollections of Berlin.

Despite Dietrich’s initial skepticism, the documentary’s international success, including an Oscar nomination and accolades from film critics, surprises her.

This success prompts her to acknowledge the documentary’s impact, leaving a message expressing her satisfaction with their disagreements.

Subsequently, Dietrich’s final memoir, “Marlene,” complements the documentary, providing further insight into her life.

Schell’s compelling film warrants a remastered and expanded reissue, as the existing edition lacks special features beyond a photo gallery.

People also viewed Blu-Ray And DVD Review Round-up: Films By Hu Bo, Billy Woodberry, Josef Von Sternberg, and more!