“Chaplin’s Historic ‘Golden Dozen'” is a cinematic treasure, offering a remarkable compilation of some of Charlie Chaplin’s most iconic short films. A luminary of the silent film era, Chaplin’s influence on the world of comedy and filmmaking is immeasurable.

Known for his distinctive Tramp character, characterized by a bowler hat, toothbrush mustache, and a bamboo cane, Chaplin’s genius lay in his ability to blend humor with profound social commentary.

The “Golden Dozen” showcases the brilliance of Chaplin’s artistry, capturing the essence of his timeless humor, poignant storytelling, and unmatched physicality.

This collection serves as a testament to Chaplin’s enduring legacy, allowing audiences to revisit the genius of a cinematic pioneer whose impact continues to resonate across generations.

Also Read More: Luke Bickle Affair: Mike Bickle Son In Relationship With IHOPKC Department Head Wife

The Mutual Films: Chaplin’s Pivotal Mutual Film Era: A Centennial Retrospective

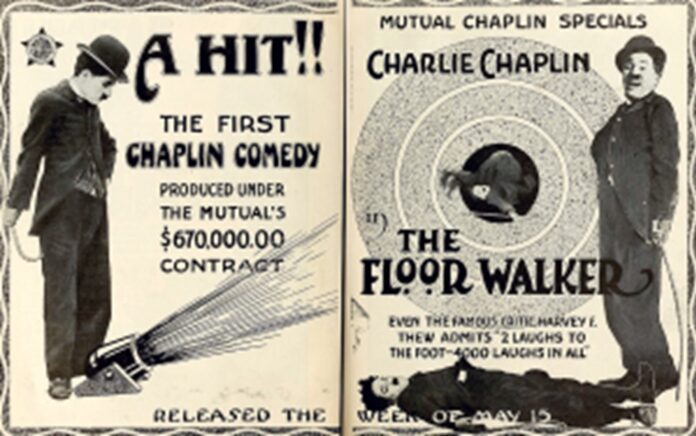

In a landmark moment a century ago, Charlie Chaplin inked a groundbreaking one-year contract with the Mutual Film Corporation.

He earned an unprecedented $670,000 and secured his status as the highest-paid entertainer globally.

This historic collaboration yielded a dozen two-reel comedies, marking a pinnacle in Chaplin’s illustrious career.

The Mutual series not only showcased Chaplin’s seriocomic brilliance but also revealed an artist at the zenith of his creative powers.

As we chronologically explore the 12 shorts, starting with “The Floorwalker” (May 1916) and “The Fireman” (June 1916), Chaplin’s remarkable evolution as a filmmaker and performer unfolds.

The series reflects a departure from the rough-hewn quality of his earlier Keystone and Essanay shorts, presenting a more refined style regarding set design and cinematography.

Adding Eric Campbell as Chaplin’s formidable adversary adds depth to the narratives, establishing a unique and dynamic rapport that defines the Mutual series.

While Chaplin maintains a foundation in slapstick tradition, “The Floorwalker” and “The Fireman” delve into societal critique, exposing corruption and fraud with a playful anarchy that marks a significant thematic expansion in Chaplin’s comedic repertoire.

Charlie, an unexpected hero in both films, ironically becomes the savior of institutions facing ruin, yet his actions have a perceptible detachment.

In his critical study “The Silent Clowns” (1975), Walter Kerr observes that Chaplin’s ability to engage wholeheartedly in various activities is marvelous.

Still, it becomes shattering to realize that his heart isn’t truly invested.

During this phase of his career, Chaplin tailored his performances to audience expectations, aligning with traditional slapstick until the success of “The Floorwalker” and “The Fireman” was established, given his substantial salary.

However, with the proven success, Chaplin took significant creative leaps.

In “The Vagabond” (July 1916), photographed mostly outdoors, Chaplin moves towards straight drama in the tradition of D.W. Griffith.

Portraying a street musician, Charlie rescues a girl (Edna Purviance) kidnapped by cruel gypsies.

The film showcases Chaplin’s inventive camera work, particularly in a skillful tracking shot from inside a moving caravan during the gypsies’ pursuit.

Camped along a country road, Charlie cares for the girl in a paternal, non-romantic manner.

The narrative takes a dramatic turn when the girl falls in love with a traveling artist, leading to the discovery of her portrait at an exhibit by her wealthy mother.

The artist aids the mother in locating her daughter, and in a departure from the traditional Chaplin ending, the girl orders the driver to turn back and pulls Charlie into the car.

However, it remains uncertain whether he can coexist in this more upscale environment.

Chaplin’s Social Commentaries Unveiled: The Unique Dynamics of “The Vagabond” and “One A.M.

In “The Vagabond,” despite its enigmatic conclusion, Charlie Chaplin introduces stark cultural contrasts that would become recurring social themes in later Mutual comedies and feature films like “The Kid” (1921) and “City Lights” (1931).

While the film doesn’t quite strike the ideal balance between humor and drama, it stands out as one of Chaplin’s most unconventional works.

Following this, “One A.M.” (August 1916) becomes a solo venture for Chaplin, showcasing his pantomimic virtuosity as he grapples with inanimate objects in a one-person display.

Despite Chaplin’s comic prowess, the film’s claustrophobic setting and single-joke premise can feel monotonous.

“The Count” (September 1916) sees Chaplin returning to familiar territory, portraying a tailor mistaken for a count in a satire of high society.

Departing from the typical rich-poor dynamic, Chaplin humorously exposes the pretentiousness of the upper class, foreshadowing the anarchic irreverence of later comedians like the Marx Brothers.

In contrast to previous Mutual films, “The Count” showcases a remarkable surge in vitality and comic precision.

The escalating battles between Chaplin and Campbell reach a climax in a brilliantly timed ballet of physical violence, featuring an abundance of kicking and acrobatic chasing that surpasses the standard for two-reelers.

After over two years and 38 short films, this film solidifies Chaplin’s distinctive stylistic fusion of direction and performance, marking it as a defining feature in the Mutual series.

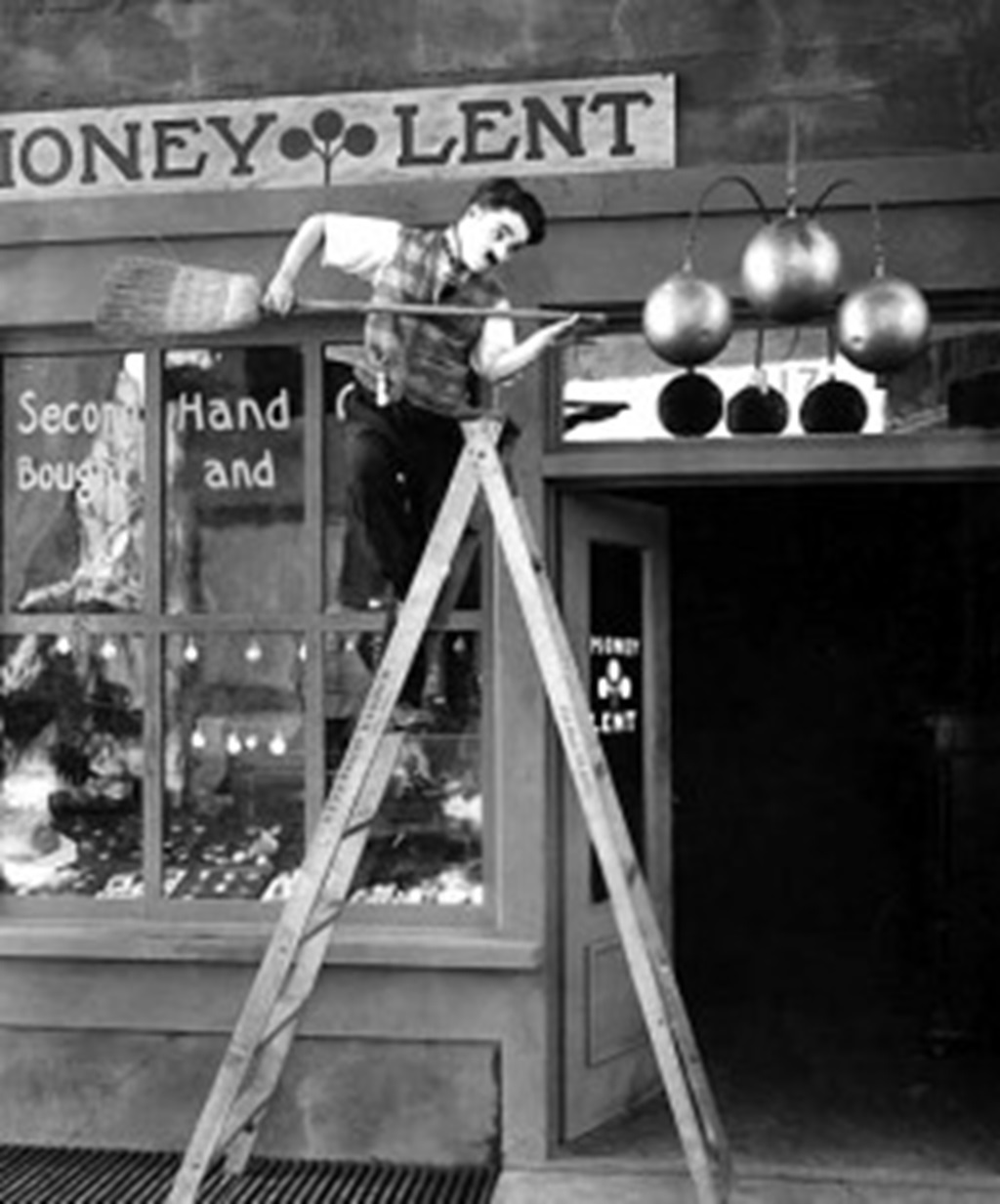

Ranked among the finest Chaplin comedies for sustained inventiveness, “The Pawnshop” (October 1916) stands out, particularly in Chaplin’s innovative use of props.

Portraying a pawnbroker’s assistant, Charlie creatively employs objects ranging from stale doughnuts to an alarm clock in need of a surgical procedure.

Notably, if a rope lies on the floor, Chaplin traverses it with the grace of a high-wire artist, showcasing an effortless and balletic performance rarely matched in his later films.

A revealing moment in “The Pawnshop” occurs in the final shot, where Charlie emerges from a trunk to apprehend a thief.

In a single remarkable take, he bows to the camera, embraces the pawnbroker’s daughter, and delivers a swift back-kick to his rival.

Beyond the flawless timing and choreography, this sequence exemplifies Chaplin’s playful detachment even in a heroic situation.

Chaplin’s Evolving Persona: A Shift in Comic Detachment and Playfulness

Regrettably, Charlie Chaplin relinquished much of his comic detachment after parting ways with Mutual, gradually transforming into a more self-conscious performer, seemingly driven by a desire to conform.

Notably, his post-mutual films, “The Pilgrim” (1923) and “Modern Times” (1936), stand out as the best examples. In these instances, Chaplin sheds some of his pathos, recapturing the exhilaration of playfulness.

This lack of pretentiousness serves as a consistent theme throughout the Mutual period. “Behind the Screen” (November 1916), a lighthearted satire on moviemaking, harkens back to Chaplin’s Keystone days.

Despite being a routine effort, the film includes a notable reference to homosexuality, a surprising and uncommon portrayal for its time.

Conversely, “The Rink” (December 1916) offers a bravura showcase of Chaplin’s versatility.

Beyond showcasing the Little Fellow as a remarkably agile skater, Chaplin’s engaging performance turns the film into a hilarious ballet on wheels.

With its colorful ensemble cast, including Austin and Bergman in dual roles, “The Rink” remains one of the best-known Mutual shorts—a timeless slapstick gem and an ideal introduction to Chaplin’s comic artistry for those unfamiliar with his work.

By 1917, Chaplin had evolved into more of a perfectionist in his approach to filmmaking, leading to missed contractual deadlines as he dedicated additional time and effort to his final Mutual releases.

Despite the extended wait for exhibitors, the outcomes proved well worth the extra time and expense.

“Easy Street” (February 1917), Chaplin’s inaugural masterpiece, foreshadows elements of social criticism that would later permeate his feature films.

The work provides a compelling portrayal of urban poverty, marked by realistic sets and a harsh tone, notably established in the dramatic opening scene depicting Charlie in a destitute state.

In a satirical commentary on religion, Charlie undergoes a “reformation” by a young mission worker (Purviance), leading him to return a stolen collection box.

Encouraged to perform good deeds, Charlie courageously joins a struggling police force and is assigned the perilous task of patrolling Easy Street, a gang battleground dominated by the towering Bully (Campbell in kabuki-style makeup).

The ingenious tactics employed by Charlie to overcome the Bully stand out as the pinnacle of on-screen moments between Chaplin and Campbell, highlighting the exquisite pacing of this short film.

Don Fairservice’s 2001 book, “Film Editing: History, Theory and Practice,” provides valuable insights into Chaplin’s editing methods in “Easy Street” and his remaining three Mutual comedies.

Chaplin’s Culmination at Mutual: A Spectrum of Cinematic Brilliance

The closing chapters of Chaplin’s Mutual period reveal a stark contrast between the somber ambiance of “Easy Street” (February 1917) and the exuberant hilarity of “The Cure” (April 1917).

In the latter, a satirical take on sanitarium life, Chaplin’s portrayal of an inebriated gentleman wreaks havoc.

After his liquor contaminates a health spa, it offers a delightful showcase of his comic drunkard mastery, complemented by Campbell’s performance as a gout-ridden patient.

The film stands superior to “One A.M.,” presenting a comically absurd yet entertaining record.

A pinnacle in Chaplin’s Mutual era, “The Immigrant” (June 1917) masterfully weaves pathos and humor, narrating the poignant reunion of two impoverished immigrants, Charlie and Edna, in a modest restaurant.

This two-reel masterpiece achieves a narrative seamlessness unmatched by Chaplin in later works.

The film’s unique chemistry, evident in Chaplin’s rapport with Purviance, adds soul and depth, conveying emotional impact without relying on title cards.

Notably, social commentary emerges as the immigrants, ironically treated like cattle during their ship’s passage by the Statue of Liberty, foreshadow the political troubles leading to Chaplin’s exile in 1952.

Despite these darker undertones, “The Immigrant” remains Chaplin’s most humanistic and endearing film, personally touching him more than any other.

In conclusion, the Mutual series “The Adventurer” (October 1917) stands out as the most popular and marks the final appearance of Eric Campbell, who tragically died in a car crash two months after release.

This slapstick par excellence features Chaplin as an escaped convict engaging in heroic deeds while navigating a wealthy family’s home.

Shot partially in Malibu, the film showcases inventive chase sequences, bookending the temporary refuge in high society.

As a farewell to the two-reeler era, “The Adventurer” marks the end of 18 months of unparalleled creativity and self-assurance.

While Chaplin’s later films expanded in length and expression, few could recapture the exuberance in The Mutuals—a body of work that remains an indispensable part of film history.

Also Read More: Gina Krasley Wikipedia And Age: How Old Was My 600-Lb Life Star?