Budd Boetticher, the maverick maestro of the Wild West on celluloid, rode the plains of Hollywood with an audacious spirit, leaving an indelible mark on the Western film genre. Follow up till the end for the details about him.

Budd Boetticher, the enigmatic auteur of the cinematic frontier, carved a trail of unparalleled artistry through the rugged terrain of Western film.

With a daring spirit and an unbridled vision, he forged an indelible legacy through his iconic collaborations with Randolph Scott, etching tales of grit and honor onto the silver screen.

Boetticher’s oeuvre is a timeless testament to his mastery of capturing the Wild West’s untamed essence.

Also Read More: Haskell Wexler and the Making of ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’

Budd Boetticher: Films Differ From Other Film Makers

When I began crafting my book “Lee Marvin: Point Blank” in 1994, I did not anticipate its publication journey would span nearly two decades.

However, this fortunate delay afforded me the invaluable opportunity to engage with luminaries who had collaborated with Lee Marvin but have since departed.

One such luminary was the maverick filmmaker Budd Boetticher, whose passing in 2001 marked a poignant loss.

Although long underestimated by Hollywood, Boetticher’s raw cinematic genius experienced a renaissance in his twilight years, earning accolades from diverse filmmakers.

Including Clint Eastwood, Martin Scorsese, and Quentin Tarantino, who immortalized him through Michael Madsen’s character in Kill Bill.

Boetticher’s films, particularly his Westerns, exuded a distinct austerity, occupying a stylistic realm between Sam Fuller’s tautness and John Ford’s grandiosity.

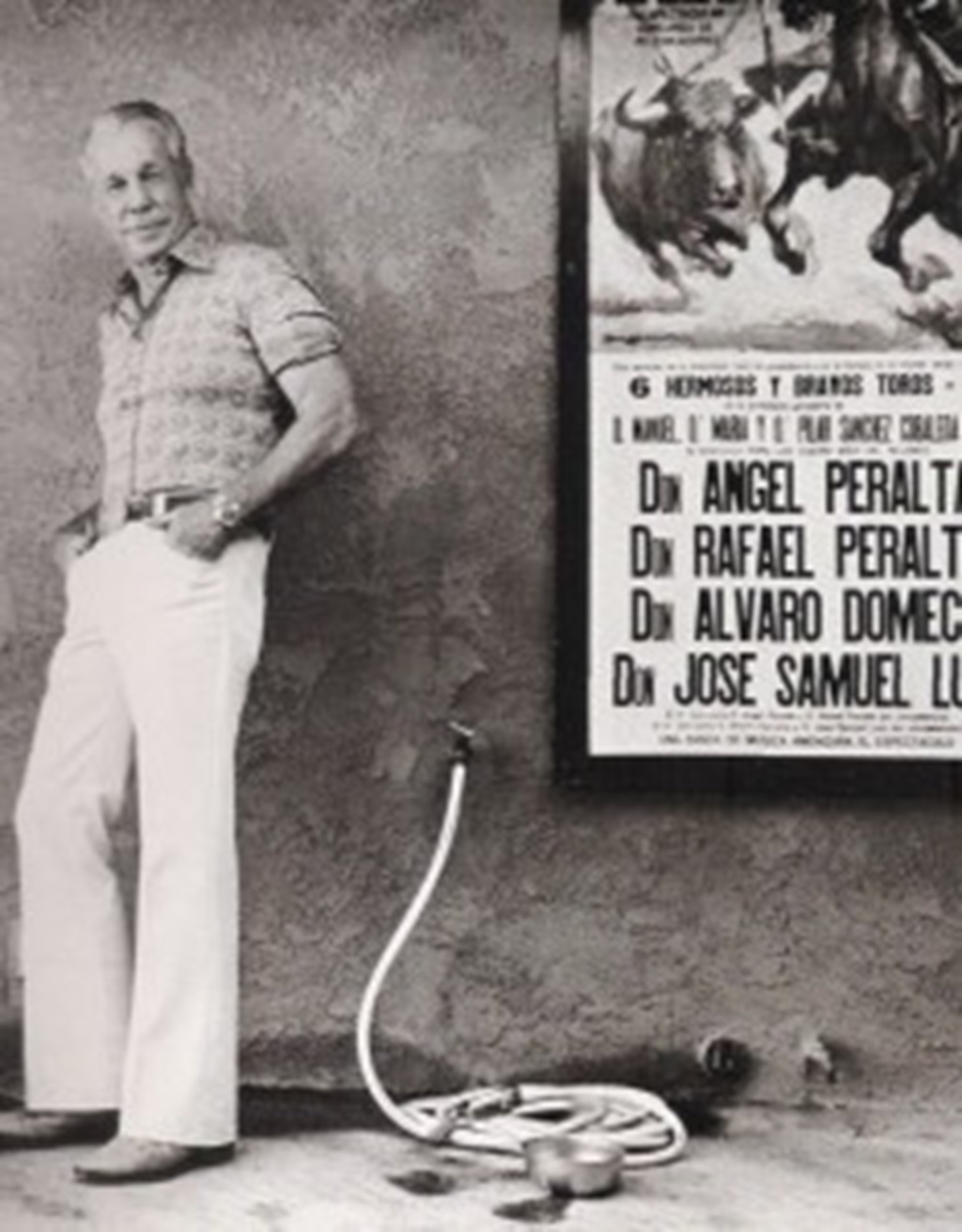

His narrative, replete with athletic exploits, bullfighting endeavors, brushes with the law, and a self-imposed vacation to Mexico, could be a captivating cinematic tale.

Despite formidable setbacks that would have daunted a lesser individual, Boetticher’s unwavering spirit and enduring optimism remained resolute until his final days.

In a captivating rendezvous on October 30, 1994, I engaged in a telephonic tête-à-tête with him for my upcoming book.

Beyond his enthralling tales of collaborating with Lee Marvin, his anecdotes proved to be a treasure trove in their own right.

Recognizing the allure of his narratives, World Cinema Paradise also saw fit to showcase the interview, unaltered and in its entirety, for the first time.

This unveiling promises to shed new light on his story, offering an unprecedented glimpse into his world.

Interview Glimpse

Dwayne Epstein: Good morning, Mr. Boetticher.

Budd Boetticher: Hello, Dwayne. You’re up bright and early.

DE: Actually, I thought I was calling a little late.

BB: Sounds like you forgot to set your clock back.

DE: (Pause) Geez, I forgot all about it! I guess I’m on time, then [both laugh]

BB: You wanted to talk about Lee Marvin, right?

DE: Absolutely. You made two films with Lee Marvin, right? Seminole (1953) and 7 Men from Now (1956)?

BB: Yes, I did. Four or five films I made with Randy (Scott) are back in theaters, not just on video. ‘They’ve been re-released in Europe on the big screen where they belong.

DE: Do you recall which ones?

BB: Sure. Ride Lonesome (1959), Buchanan Rides Alone (1958), The Tall T (1957), and Comanche Station (1960). I haven’t seen them in a while, and the Director’s Guild held a retrospective recently. I must say they’re pretty darn good.

DE: That’s terrific! Before we go any further, I just wanted to tell you that the gangster film you made is one of my favorites…

BB: The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond (1960). with Ray Danton. That also had a young Warren Oates and Dyan Cannon making their debuts.

DE: Very cool. So, the first picture you used Lee in was Seminole, right?

BB: Exactly. He portrayed Sgt. Magruder delivered an outstanding performance.

Burt Kennedy was the one who brought him in. He recommended Lee to play the second lead in my next film with Randy [Scott].

Now, Duke Wayne [as producer], and you can quote me on this: Duke was either a tough cookie or the most loyal friend you could have, depending on his mood.

Burt asked Duke, “Who should we use?” Duke said, “Let’s use Randy. He’s through.”

DE: [laughs] Well, that was considerate of him.

BB: Yes, well, in every Randolph Scott movie, there was always a breakout star because Randy didn’t mind. But Duke… was a different story.

DE: How was Lee Marvin to work with on 7 Men from Now?

BB: He was exceptional. Being a former Marine, he had a real grasp on handling firearms. I wanted to introduce something unconventional in a Western.

I had never seen a gunfighter practicing his draw while, say, urinating in a Western before. So, whenever possible, I had Lee rehearse and practice his drawing.

His demise was incredibly poignant when Randy shot him because of that. He stood there for a moment, staring at his gun in disbelief.

The audience adored it. The reaction during the preview at the Pantages was unprecedented. They even halted the film and replayed the scene.

DE: Wow, that’s genuinely innovative. I’ve never heard of that being done before.

BB: Yeah, the sneak preview — can you believe it? It was a double bill with Serenade (1956) starring Mario Lanza.

Not a soul in the audience was under forty. The theater’s marquee only mentioned Serenade.

I turned to John Wayne and exclaimed, “Good Lord, Duke!” Initially, people started leaving when they realized it was a Western starring Randy.

However, once it started, they stayed and truly relished it. Yes, but Lee was phenomenal.

DE: Did you ever consider collaborating with him again after that?

BB: Actually, I penned Two Mules for Sister Sara (1970), envisioning him in the lead.

The turning point was when I saw Lee in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), and, to be frank, I thought he was inebriated. Be careful how you phrase this part. Anyway…

DE: I spoke with Woody Strode, who mentioned that Lee was intoxicated.

BB: How’s Woody doing? I collaborated with him on City Beneath the Sea (1953).

DE: He’s holding up well. He’s a kind soul and shared a lot of insights. He still resides in Glendora, but he spends a lot of time alone now.

BB: Well, can you please give him my contact information? I’d love to reconnect with him.

DE: I definitely will. So, you suspected Lee was intoxicated in Liberty Valance?

BB: Well, that was the speculation. I inquired around and verified it through others. I felt he drank excessively and couldn’t envision working with him.

DE: What happened to the script?

BB: Universal eventually produced it, but they botched it. I can’t officially say this, but Eastwood’s character would have to be oblivious not to notice alcohol and cigar odors on her breath.

In my rendition, she was a courtesan, not a prostitute [Shirley MacLaine’s character is a prostitute disguised as a nun]. Years later, I discovered that Martin Scorsese admired my work and sought memorabilia.

I stumbled upon the original screenplay for Sister Sara, which was over twenty years old and falling apart. I had to make a copy as it was disintegrating.

I sent the original and a copy to Scorsese and kept one myself. I revisited it and found it to be exceptional. Let me share a humorous anecdote. A few years back, it aired on late-night TV, and around 1 a.m.,

I received a call from a gruff voice asking, “I missed the credits. Did you direct this lousy Sister Sara I just watched?” I replied, “No, I only wrote the screenplay…” The voice said, “Good!” and hung up. It was John Ford.

[Both laugh]. Okay, what else do you want to know about Lee Marvin?

DE: You mentioned you didn’t want to collaborate with Marvin.

BB: Well, I heard he had a drinking problem.

DE: [Stuntman] Tony Epper called him a bottle actor. He believed Marvin did his best work when he drank.

BB: I don’t buy that. You can be dedicated without alcohol and unwind after five, like everyone else.

Duke had a [screenwriter] friend named James Edward Grant. He aspired to direct but felt he couldn’t without a drink. That’s nonsense. No actor performs better after a few drinks.

They’re usually on their fifth drink by then and can’t complete the film.

DE: Did you ever consider him for anything else?

BB: Not really. I’ve been working on a book about bullfighting called When in Disgrace. You should give it a read sometime.

I believe it’s available at Samuel French or Larry Edmunds Bookstore.

It delves into bullfighting. I entered the industry with a job most women would envy. I had to instruct Tyrone Power on bullfighting movements for Blood and Sand (1941).

When I began making westerns with Randy, I delivered what was expected. If they wanted a movie to run for an hour and 26 minutes, I ensured it was an hour and 27 minutes. It usually took just 18 days.

The remarkable aspect of those films was the scripts. Burt Kennedy worked on most of them, and we had Lucien Ballard as the cinematographer. Lucien did outstanding work for us.

Recently, there was a retrospective of my work in Dallas, and they honored me with some kind of pretentious award.

I hadn’t seen some of my films in years and was pleasantly surprised by their quality.

There were no profanities. There was no explicit kissing. The films made today… I ventured to Mexico and ceased making films.

I spent seven years in Mexico working on the book about [bullfighter Carlos] Arruza. Eventually, I developed a screenplay from it, and we’re set to commence filming soon.

DE: Well, I’m delighted it worked out well for you.

BB: You see, the remarkable aspect of my career is that I never received an Academy Award, an Emmy, or any of those accolades.

The Los Angeles Film Critics Association honored me with the Career Achievement Award 1992. That meant a lot because it’s not something to be taken lightly.

[Laughs] They may not agree much, but they unanimously voted for the Career Achievement Award.

DE: That’s truly an honor. It’s interesting how you weren’t fully appreciated before, but now…

BB: Yes, if you stick around long enough. It’s amusing. I directed 37 films; only ten were Westerns, yet I’m labeled a Western director.

I made several gangster films and am now considered a gangster director.

DE: What led to your decision to stop directing?

BB: I didn’t believe resorting to profanity was necessary to develop a character. I didn’t want to be part of that kind of filmmaking.

However, I’m back at work now. I waited for the right project to come along. I’m set to direct A Horse for Mr. Barnum.

DE: What’s the film about?

BB: It’s a true story about P.T. Barnum acquiring several Andalusian horses and the cowboys he hires to return them.

DE: That sounds intriguing. Do you have a cast lined up?

BB: We’ve got Robert Mitchum playing Barnum and Jorge Rivero, a major star in Mexico, portraying one of the cowboys.

James Coburn is also part of the cast. We’ll be using Lippizans.

DE: I’ll be eagerly anticipating it.

BB: I’m thrilled you’re writing this book on Lee Marvin. He was a phenomenal actor. He brought more to a director than one could ask for.

DE: How did he get along with Randolph Scott?

BB: He got along with everybody.

DE: How did Scott get along with him? Did they establish a good rapport?

BB: Scott didn’t establish much rapport with anyone. He wasn’t the typical all-American hero type.

DE: With the square jaw.

BB: Exactly. He kept to himself. One evening, while having dinner with Burt after shooting that day, he asked, “Who’s the kid in the red underwear?” I said, “James Coburn.”

He replied, “He’s pretty good. Write him some more lines.” In six of the seven pictures I made with Randy, the second lead stole the show.

No one would have cared if the second lead had killed Randy, unlike in a John Wayne picture. The second lead often achieved significant success after working with Randy.

We had Richard Boone, Pernell Roberts, James Coburn, and many talented actors.

DE: It certainly sounds remarkable.

BB: Let me share a humorous anecdote about Richard Boone. He was starring in the TV show Medic, and I wanted to cast him in the film I was working on with Randy called The Tall T.

I wouldn’t have faced any issues if Harry Cohn was still in charge. However, Sam Briskin was overseeing Columbia, and he told me, “You don’t want Boone.

He’s got no sense of humor and all kinds of pockmarks…” I had to find out for myself.

I called Boone and told him I wanted him for a film. I mentioned Briskin’s comments about his lack of humor. Boone’s response was, “I guess he doesn’t think heart operations are pretty damn amusing.”

DE: [Laughing] He seemed to have quite a sense of humor. Your career resembles Sam Fuller’s in that you both received recognition later.

BB: My agent, who happens to be Jewish – probably why he’s so adept at his job – secured a three-picture deal for me. He remarked, “You know, you’re the Gentile Sam Fuller.”

I responded, “I’d prefer to be the Jewish John Ford.”

Also Read More: DVD Review: “Hollow Triumph” (1948)