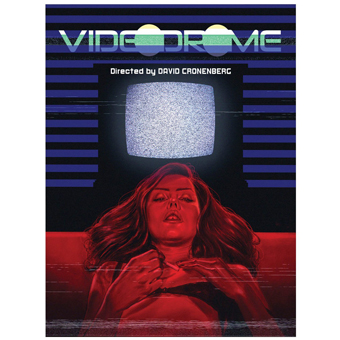

Videodrome

Region B Blu-ray + PAL DVD

Arrow Video (UK)

1983 / Color / 1:85 widescreen / 89 min. / Street Date August 17, 2015 / £28.17

Starring James Woods, Sonja Smits, Deborah Harry, Peter Dvorsky,

Leslie Carlson, Jack Creley, Lynne Gorman, Julie Khaner, Reiner Schwartz, David Bolt.

Cinematography Mark Irwin

Art Direction Carol Spier

Film Editor Ronald Sanders

Original Music Howard Shore

Written by David Cronenberg

Produced by Pierre David, Claude Héroux, Victor Solnicki

Directed by David Cronenberg

When certain movies get re-issued with perhaps one extra feature added to the mix, web reviewers will start complaining about ‘double dipping.’ But the custom selection of extras offered by a number of disc companies is sometimes so good that a reissue becomes irresistible. Many Criterion releases qualify for this, of course. Over in England, Arrow Video has been putting out Region B discs of American movies that frequently better the available domestic versions. This David Cronenberg shocker was thoroughly covered in an expansive Criterion disc from 2010, yet Arrow has put together a highly desirable collection of new extras.

Movies have gotten far rougher and tougher in the last 32 years, yet 1983′s Videodrome still has what it takes to creep people out of genuinely dangerous ideas. Its McLuhanesque, Ballardesque merging of man and media still provides real food for thought — it remains dangerously radical on the intellectual plane. Videodrome is also core science fiction. Writer-director David Cronenberg pioneered queasy body-horror Sci-fi, and with this effort, he scored even higher as a purveyor of bizarre intellectual concepts. In a movie, he introduces the first fully realized virtual reality world (forget Tron). Cronenberg ladles out more disturbing ideas than had ever seen the light of a movie granted major distribution: insidious technology, underground video, porn, violence, sadomasochism, and snuff movies.

They’re all in the service of a concept that, in maturity, was light-years ahead of the competition. Readers of fare like Philip K. Dick’s The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch possibly felt right at home, but much of the mainstream 1983 audience was lost, lost, lost.

Cronenberg’s script begins with a man looking for new experiences and new sensations. Soft-core cable entrepreneur Max Renn (James Woods) is hot for edgy material. His tech assistant Harlan (Peter Dvorsky) succeeds in tapping into an illegal satellite transmission of an all-torture, all-murder TV signal called Videodrome. Max dispatches porn agent Masha (Lynne Gorman) to find it for his cable channel and personally follows the trail to Bianca O’Blivion (Sonja Smits), the daughter of video cult visionary Brian O’Blivion (Jack Creley). Techno-guru Brian seemingly exists only on videotape. Through the medium of TV, he dispenses weird wisdom about a new age in which people will physically merge with the virtual video world. Max also becomes attracted to radio psychologist Nicki Brand (Deborah Harry), a masochistic sensationalist who introduces him to mild S&M. When Nicki discovers Videodrome, her response is to seek out the video horror show immediately — because she wants to become a ‘contestant.’

David Cronenberg’s erratic string of exploitative shockers before Videodrome always had strong core ideas. Shivers and Rabid’s grandiose concepts overshadow their grindhouse content, going far beyond mere nudity and gore. Shivers is a gloss on Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Scanners hit the commercial jackpot with a hybrid of Philip K. Dick’s expanded-consciousness worldview. Super-powered minds can invade other minds to control and destroy, but finer implications give way to chase scenes and exploding heads, surefire audience-pleasing material.

Videodrome recycles a sampling of Cronenberg-favored motifs: strange new body orifices, exploding bodies, and technological conspiracies to transform mankind. This time around he adds the Dickian idea of altered reality. The Videodrome video signal is like Palmer Eldritch’s drug “Chew-Z”: we experience Max Renn’s disconcerting hallucinations as his mind is altered. Max becomes a classic surreal hero, much like Buñuel’s Archibaldo de La Cruz or Freda’s The Horrible Dr. Hichcock, exploring new conceptual territory with his eyes wide open. Cronenberg’s later revisionist re-think of the 1958 classic The Fly has the same transgressive hero. A transformation into a monster becomes a voyage of grotesque but miraculous possibilities. As he outgrows his human form Seth Brundle is forced to confront both mortality and the alien-ness of his own body. A similar Quatermass-like process in Videodrome changes Max Renn from the inside out. He, too, must learn to embrace an unknown future that he calls ‘the New Flesh.’ Scientific progress blends with spirituality when the ultimate escape from ‘the old flesh’ becomes all too literal.

After a slow start in his earlier thrillers, Cronenberg hits his directing stride with Videodrome. For the first time his actors are all top-rank and optimally cast. The effects don’t overpower the story, which doesn’t rely on a chase to sustain a commercial thriller framework. The revelations are well-paced, helping us to absorb some truly weird happenings. A television is transformed into a veined and pulsing sexual organ; Max Renn pulls an organic pistol from a vagina-like slit in his stomach. In essence, Cronenberg shows man using medical and media technology to explore a new world. But in every case, taking the voyage means transforming mentally, physically, and spiritually. Only the initial steps are voluntary. Max Renn is on a slippery slope from the moment he takes those first few steps — there’s no going back. He’s an explorer in an unknown world, like the Shrinking Man.

James Woods proves perfectly suited to playing a sympathetic character who nevertheless is a voyeur and smut peddler. Ordinary soft-core attractions don’t do anything for him. The little touches he gives the role become funnier on repeated viewings. Deborah Harry’s Nicki Brand makes a convincing masochist and generates the erotic connection Cronenberg needs. A surreal heroine, Nicki goes straight to the center of her obsession and never looks back. Her early exit to become a virtual presence probably sparked resentment among the fan base that wanted a flesh & blood Blondie to stick around longer, and indeed, a perfect Videodrome would want to chart her ‘explorations,’ too.

Among the excellent supporting players is Lynne Gorman, whom Cronenberg manages to make intriguing just by allowing a woman older than fifty to have a sexual appetite without being humiliated for it. Cronenberg plays with light comic irony as well. At one point, Max Renn tries on a pair of dark-framed glasses and, for a second, ‘transforms’ into a substitute David Cronenberg. While escaping through an alley, Renn passes workers moving a series of doors. Are they a visual pun for the ‘doors’ of consciousness?

But what we most remember are the bizarre instances where erotic and technological taboos merge. Max Renn can have physical sex with a pair of lips on a television screen. His ‘stomach vagina’ can hide a weapon. Cronenberg’s illusions go a step beyond classical film surrealism, as we share the subjective sensations of the surrealist adventurer. Some concepts aren’t as well established. In one scene Renn’s obscene gun-arm (shades of The Quatermass Xperiment) is meant to shoot not bullets but instant-growing cancerous tumors.

There’s also the gross ending where a virtual Deborah Harry shows Max Renn the next step in his personal evolution. Nikki might as well be speaking to Max from within The Matrix. His crossover is accomplished by imitating something he sees on television. Cronenberg’s ideas in these early films were ‘way, way out there’ in the best possible meaning of the term. They’re always driven by a coherent interior logic.

Arrow Video’s Region B Blu-ray + PAL DVD of Videodrome has a clean transfer of a truly brilliant movie — and brilliant not merely because intelligent and challenging sci-fi has become so rare. Cronenberg makes the horror exploitation genre communicate ideas difficult to understand in doctoral papers about the media-scape. The movie is billed as a ‘restored HD unrated version,’ which, as far as I can tell, is identical to earlier video versions. Bits were added back in almost as soon as the movie hit home video long ago.

A comparison with the earlier Criterion disc sees several of its extras ported over. Director and actor commentaries have not been retained; they’re probably Criterion-specific. Arrow did find an interesting 20-minute piece on Cronenberrg for Brit TV called David Cronenberg & the Cinema of the Extreme. Cronenberg concisely describes his theories, while directors George Romero and (a very animated) Alex Cox talk about the need for some form of rating system. The always-refreshing Cox energetically slams the movie Se7en as reprehensible trash, a surprise that had me jumping up in approval. I’m probably a prude, but there’s a difference between compellingly disturbing ideas and empty exploitation.

Most of the other extras are familiar — a Cronenberg short subject from 2000, Michael Lennick’s clever and impressive features about the special effects. Videodrome seems to have had unlimited un-filmed but fully worked out visual effect hallucinations, some of which we see in BTS footage, as temp video displays or make-ups under construction. Alternate scenes for TV are here, along with Samurai Dreams, etc.. I still like the 1981 roundtable interview with Cronenberg and fellow directors John Carpenter and John Landis. At the time all were making fantastic films. The least demonstrative of the three, Cronenberg seems the only one with “something to say.” The host is a young, bright Mick Garris of the Masters of Horror cable series.

I was especially curious to listen to Arrow’s featured exclusive extra, the promised Tim Lucas commentary. It doesn’t disappoint. Cronenberg synthesized a lot of radical thought into a consistently coherent series of film fantasies; that he tapped Lucas to report from the set convinces me that he deemed the young fan writer capable of grasping what was happening. There are a lot of edgy abstract ideas to consider, many of them unsuited for discussion in People magazine. The show is an invitation to ponder the convergence of humans and technology and how we use ‘media gratification delivery systems’ to gratify our sex fantasies.

I usually listen to the first twenty minutes of a commentary, skip around a bit, and then listen to the end. Just as with the recent Blood and Black Lace, this commentary was too illuminating to set aside. Lucas spends only a little time on his on-set experience and instead gives us even more detailed analysis and insight into everything and everybody we see on screen. His thoughts are well organized, and his connections to possible influences deepen our interest rather than dissipate it. His personal extrapolations are also engaging. I think Videodrome will persist as a great work of futurism. I know for certain that I haven’t grasped its full importance. Lucas’s comments ring true, especially his observation that contemporary culture is in a Cronenberg-predicted transformation: we are indeed being absorbed by our technology. Heck, all the evidence suggests that Mr. Lucas is real, but through his many social media communications, he has also become an eerie, disembodied virtual person. All hail the new Facebook Flesh.

A second pair of Blu-ray and DVD discs contain four early Cronenberg films, all beautifully restored. The medical student-turned-filmmaker has an awkward beginning, distinguished from ‘normal’ film students only in that the philosophical speeches indicate he has ‘something to say,’ even if he hasn’t found the ways to express himself in film. Considering the depth of his later feature work, this should encourage all aspiring filmmakers who haven’t yet mastered camera grammar. The third and fourth pictures are more professional and use a few actors and modernistic buildings to impart a futuristic look. Stereo is the one really accomplished work here; I gave my thoughts on it in a review for Criterion’s 2014 release of Scanners. The color Crimes of the Future is more similar but less compelling overall. Ronald Mlodzik (Adrian Tripod) returns as the main character, who still dresses like Peter Cook’s devil from Bedazzled. The final scene becomes really queasy, with just a suggestion that Cronenberg is adding child molestation to his themes of sex and death.

The second disc’s added films are accompanied by a welcome essay-featurette with Kim Newman, who has plenty of bright comments about horror’s direction in the ’70s and Cronenberg’s individualized approach. In these early films, he was an eccentric ‘with something to say.’ When his thoughts found full expression in films like Videodrome, it was well worth the wait.

Also: The Best Movies You’ve Never Heard Of (Special Baseball Edition): “Alibi Ike” (1935)